Stay Safe: Advice from the Pennsylvania Wilds

It’s late at night. My son is in bed, and I’m writing this article while he sleeps because we’ve been together all day.

He’s been off from school, and my work has been closed, and by now you can probably see where this is going.

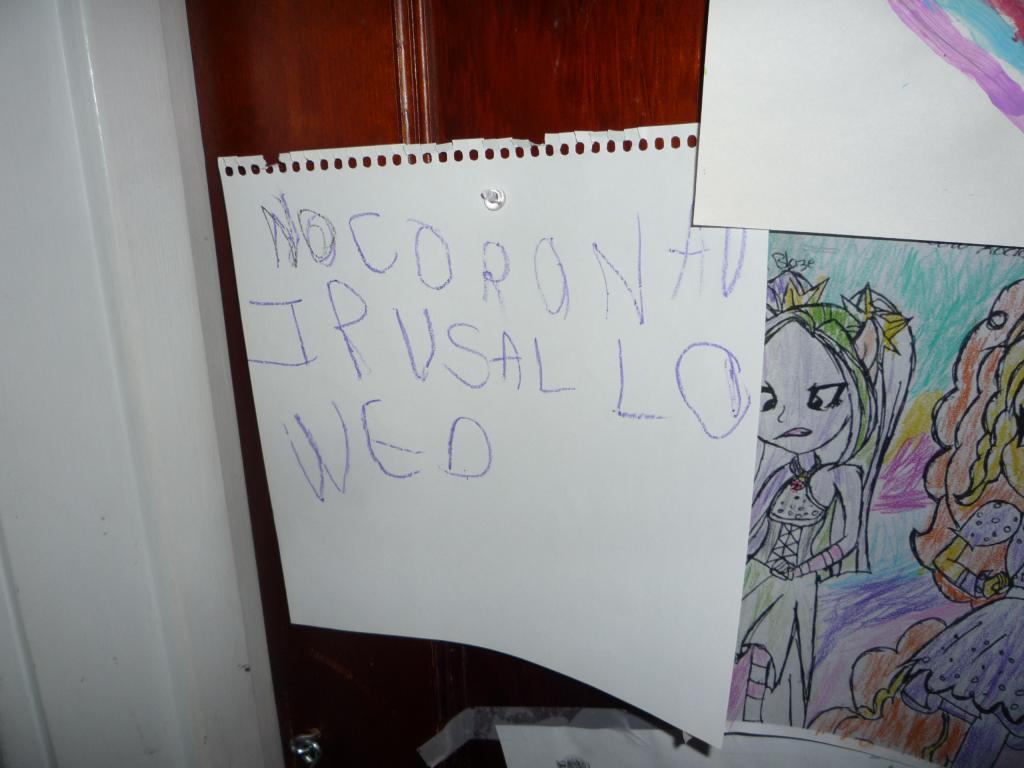

He has a hand-made sign on his door that says “No Coronavirus Allowed.”

Across the state, Pennsylvania citizens have been asked to stay inside. We’re to avoid contact with anyone, as much as we can. Stores are selling out and businesses are shutting down operations as people prepare to isolate. At home, I’ve been filling the time by teaching my son basic survival tactics. We’ve already learned how to signal for help in Morse code (three short, three long, three short) and good materials to carry to start a fire (a piece of milk carton is great; it lights up and it’s waxed, so it’s also waterproof.) You make the best of things.

It feels strange to write an article telling people to avoid the great tourism opportunities in the Pennsylvania Wilds. And yet, in this crisis, that’s what I’m going to do.

At this writing (and remember, the situation is fluid and changing very fast) the virus has not hit the PA Wilds very hard. There have been confirmed cases in Centre, Lycoming, Potter and Warren Counties, and that’s it so far. And that’s why we’re all staying indoors—If we avoid contact as much as possible, we may be able to prevent the crisis from getting much worse than this.

Traditionally, I’m known for writing about local history. And the closest thing I have to a comparison is the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918. I’ve studied that before, and there are comparisons to be made. And since I’m confined to the house and I’m easily bored, I’m going to take a moment and fill you in.

Like today, the epidemic began with travel. The Spanish Flu came into the area through railroad stations; people coming home from trips brought the flu with them. In the earliest months of the flu, many of the obituaries in the newspapers mentioned that the deceased was either the result of a railroad employee or someone recently came home from a trip. In what is today the I-80 Frontier, the flu arrived through railroad stations in Castanea and Lock Haven, and spread from there.

Up in Elk Country, people were quarantined to prevent the spread of the flu. This left local doctor L.L. Liken as the only doctor in the small community of Bitumen, attempting to care for six hundred people on his own. For two weeks, Liken worked almost around the clock, treating people as he ate and slept in short bursts, sometimes minutes at a time in the homes of his patients.

In the present-day Allegheny National Forest and Surrounds, nurses cared for patients in the Warren area in improvised aid centers; some were put in auditoriums and schools. Though they were able to save many, hundreds of patients were lost.

On a farm near Scenic Route 6, in today’s Dark Skies, local farmers allowed indigent workers to bury babies and children who had passed away in a special section of the local cemetery. (Today there is an effort to locate and identify the graves of these children, known as the “basket babies.”)

It was a dark time in our history. But we got through it. We will today, as well. In the meantime, all I can do is to repeat what everyone else is saying. Isolate yourselves and stay safe. The Pennsylvania Wilds will still be here when this is over. Though we may have to be apart for the moment, we’re all in this together.