A wise person once noted, “Mother Nature is beautiful, Mother Nature is powerful, and Mother Nature is cruel.”

Nowhere is this truer than in the Kinzua Creek Valley where, in fewer than 30 seconds, the “powerful and cruel” became real on July 21, 2003 and something “beautiful” that stood for 121 years, was gone.

It has been 20 years since the Kinzua Viaduct/Bridge was blown out by a tornado.

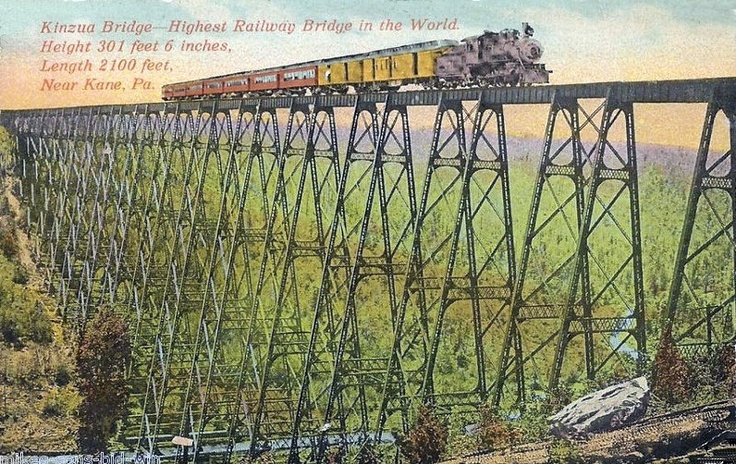

Image: Kinzua Bridge Vintage Postcard

Affectionately known as “The Eighth Wonder of the World,” it was one of the tallest railroad bridges in the world at 301 feet high (almost as tall as the Statue of Liberty) and 2,053 feet long.

At more than 300 feet above the valley floor, railroad men were well aware that gale-force winds howling through the Kinzua Creek Valley made crossing the viaduct frightening, if not perilous.

“I don’t like to cross the Kinzua Bridge,” a railroad man told The Bradford Era in early 1900. “Someday during a severe storm or tornado that bridge is liable to get a bad shaking up. In such a storm, trains should not by any means, attempt to cross the structure. If there ever is force enough to a storm to blow the center of the bridge out of plumb, that will settle it.”

The winds up there were strong enough to blow roofs off box cars. Trains had to stop until the winds died down. Even in ideal conditions there was a 5-mile-an-hour speed limit across the span. Erring on the side of caution, a second set of tracks was installed side-by-side to catch the wheels and keep a train from being blown over the side of the bridge.

An Ambitious Idea, From the Start

Railroads carried endless carloads of coal, timber and oil, fueling the furnaces of the industrial revolution – and the economies of many northern Pennsylvania towns whose populations exploded.

General Thomas Kane, a celebrated Civil War general and namesake of Kane Borough, was chairman of the New York, Lake Erie Western Coal & Railroad Company. He was running the rails from the coal-, oil- and timber-rich northern Pennsylvania mountains to lucrative markets in upstate New York, which were rapidly consuming vast amounts of Pennsylvania’s natural resources.

There was one problem. How was General Kane going to get his trains across the vast Kinzua Creek Valley near Mt. Jewett? Rather than bearing the astronomical cost and nightmare of laying eight miles of tracks around the valley, he chose to build a bridge and run his rails straight across it.

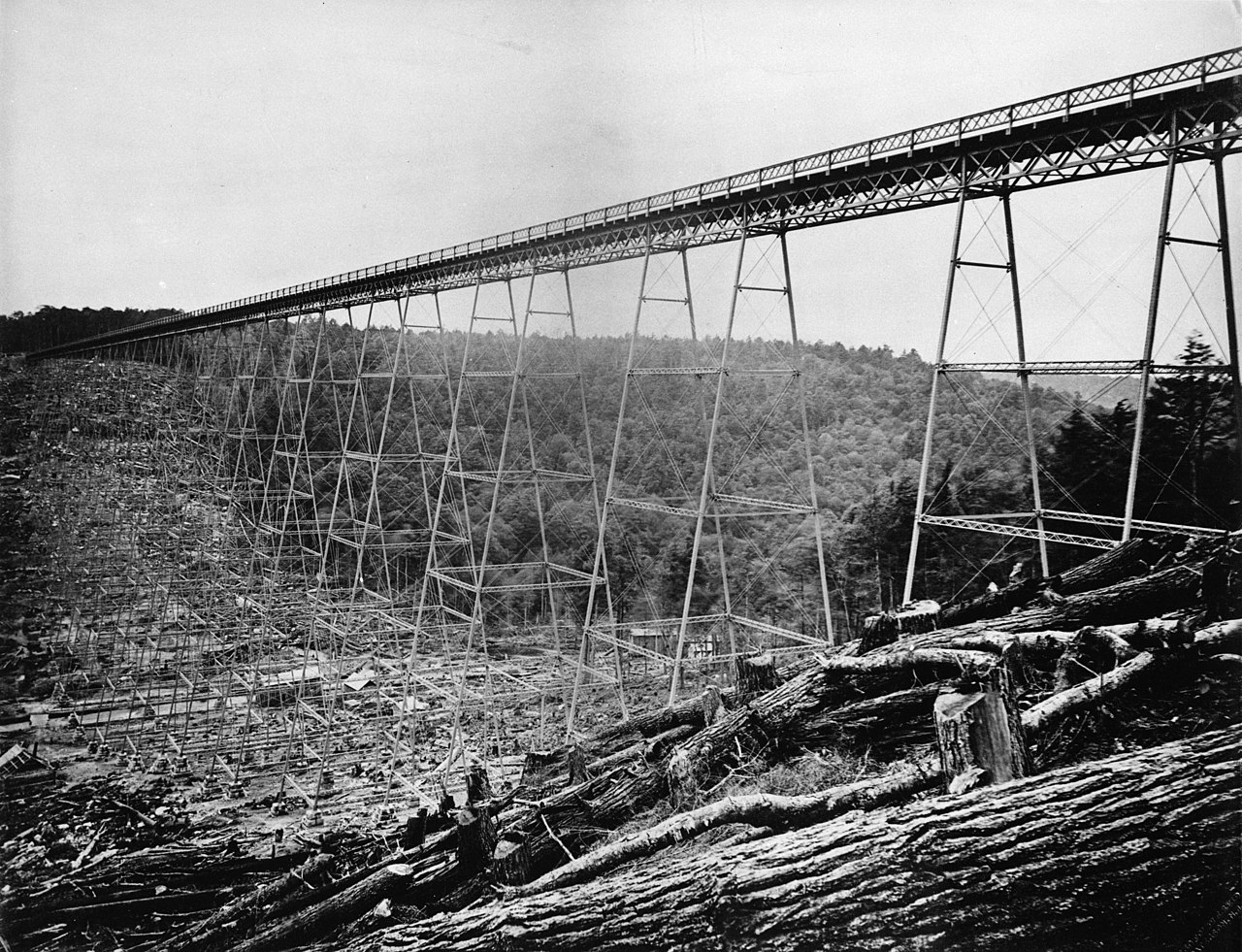

Image: Construction begins

Construction of the Kinzua Bridge/Viaduct began in 1881 with towers, decking and tracks going up in 1882. It took 40 workers only 94 days to build the 2,053-foot-long bridge with more than 15,000 tons of iron.

While people from all over the United States marveled at the “Eighth Wonder of the World,” structural engineers began to worry about the winds and the integrity of the ironwork. High winds had already blown the viaduct 2 and 7/8 inches out of line within a year of its completion.

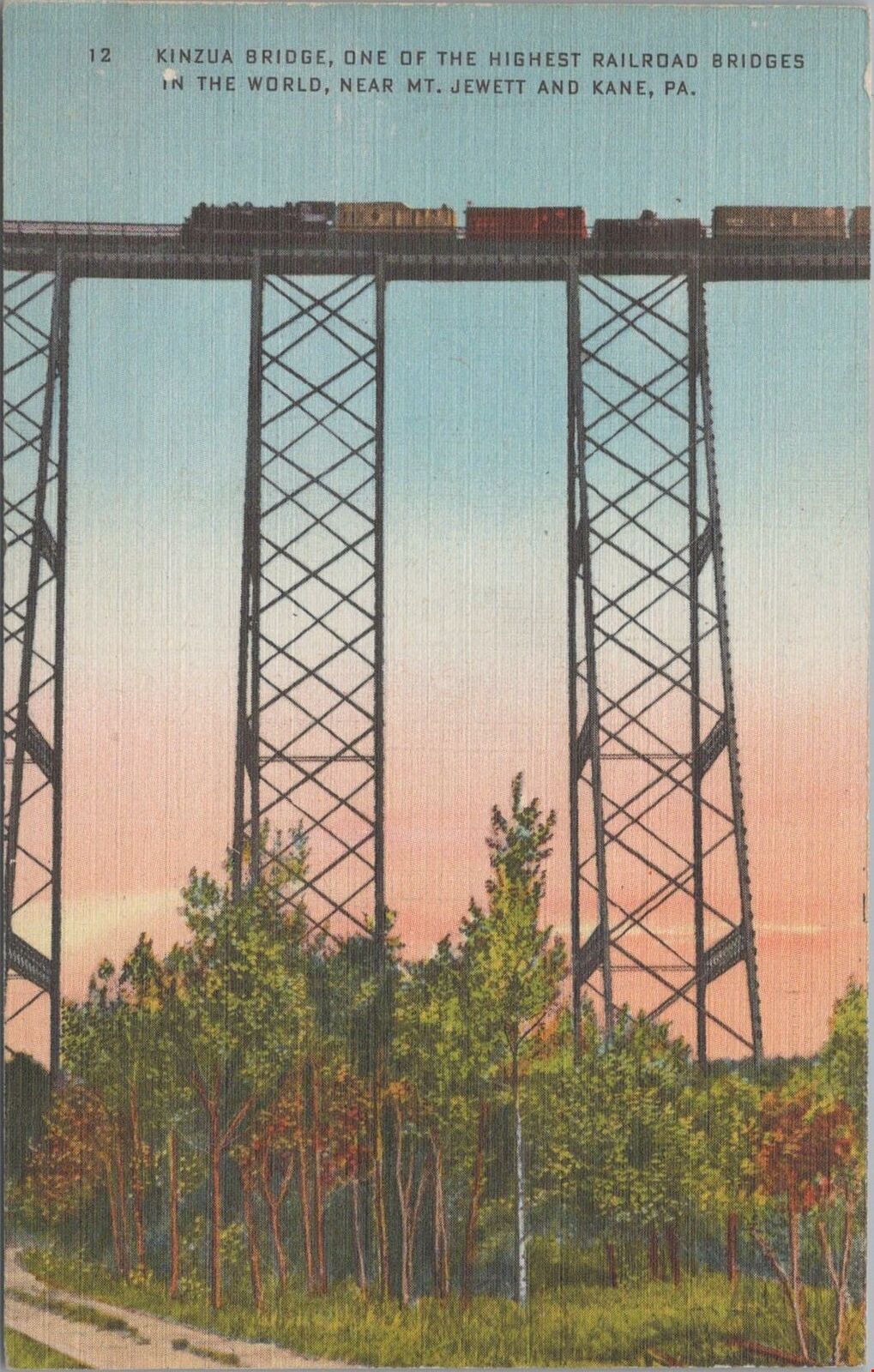

Image: “The Eighth Wonder of the World”

The bridge was also taking a beating from larger and heavier locomotives. With each crossing, the bridge would vibrate and shake.

The structure was closed in 1900 to replace the ironwork with steel. However, the original iron anchor bolts in the concrete piers were not replaced, proving costly years later. On September 25, 1900, with steel reinforcements in place, the bridge reopened to rail traffic.

The New York, Lake Erie and Western Coal and Railroad company became part of the Erie Railway system and dumped the rail line running across the bridge in 1949. Then in 1959 the Kinzua Bridge was closed and later sold to an Indiana, Pennsylvania scrap-metal dealer for $76,000. However, the scrap dealer, realizing its historic value, sold it back to the state.

This meant new life for the land around the bridge in August of 1963 when the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania bought the bridge and property creating the Kinzua Bridge State Park. It opened to the public in 1970.

Image: Vintage postcard of a Freight Train rolling across the Kinzua Viaduct

In 1987, as freight traffic faded and tourism took off, the Knox and Kane Railroad began running passenger trains loaded with sightseers across the bridge. Passengers described the ride with words like “suspended in mid-air,” “flying,” “magical,” and some said it was like “being at heaven’s door.”

More than 100,000 visitors eagerly boarded the trains every year for a thrilling ride across the “Tracks in the Sky’” to view the Kinzua Valley from dizzying heights. In 2002, things changed, and those sightseeing trains were the last trains ever to cross the Kinzua Bridge.

Image: Vintage Passenger train postcard

As Time Took Its Toll, a Tornado Took it All

In the summer of 2002, it became obvious something was seriously wrong. Sections of the bridge towers were rusting through, making it too dangerous to cross. The bridge was closed, and the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) ordered an inspection.

“Our analyses showed bridge deterioration worse than originally estimated,” said then DCNR Secretary Michael DiBerardinis. “Emergency repair of this structure is no easy task, but all parties involved are fully committed to returning foot and rail traffic to this historic landmark and popular tourist attraction.”

In February 2003, W. M. Brode Co. of Newcomerstown, Ohio, a national leader in railroad bridge repair, was hired to begin a $10.8 million fix.

Brode’s crew was hard at work on the afternoon of July 21, 2003, when a band of severe storms began thundering across the Allegheny National Forest. Brode’s project superintendent Floyd Quillin ordered his workers to leave the bridge and get out before the storms hit.

At 3:00, a mile west of the bridge, an F-1 tornado packing winds of 90 miles-per-hour touched down, snaking its way through the Kinzua Valley toward the bridge. The tornado smashed dead- center into the viaduct, taking out 11 of 20 towers and 1,200 feet of the span. The tornado lifted the center towers from their ancient, rusted anchor bolts, slamming the twisted towers to the valley floor. With a direct hit to the bridge’s gut, only six towers to the south and three towers to the north remained standing.

It was a close call for the Brode crew.

“At approximately 3 p.m., I had just sent my crew back to the motel where we were staying when severe rain hit the job compound,” said superintendent Quillin, “Myself and one crew member who rode with me were leaving the site when I heard four or five loud booms. The trees were cracking and bowing. I decided to back up the truck and find a ditch to hide in.”

He said just quickly as it hit, the tornado was gone. “Someone yelled, ‘I think the bridge came down,’” said Quillen, “It took us a while to climb through the downed trees and wreckage to a point where we could see. It looked alright at first, but when we got closer, we saw the whole middle of the bridge was gone.”

Quillin said at this point he realized the “booms” he heard were the towers hitting the ground… one by one.

Image: Kinzua Bridge in Ruins – Wikipedia

In fewer than 30 seconds, the era of rail traffic spanning the Kinzua Creek Valley was history and a bridge lasting more than 100 years was gone.

“When I heard the news that a tornado had struck the bridge and knocked down a significant portion of it, I’ll be honest with you, it was sort of like losing a member of the family,” said Gene Comoss, former director of DCNR’s Bureau of Design and Construction. “In fact, I was probably in shock when I heard it.”

When Mother Nature Hands You Lemons, You Make Lemonade

In the wake of the collapse, State Representative Martin Causer vowed every effort would be made to rebuild. “It’s crucial to the area. It’s the biggest tourist attraction in the whole region,” Mr. Causer said upon returning from viewing the devastation.

But the price tag for the rebuild was steep – $45 million. Harrisburg originally nixed the idea of rebuilding, instead proposing that the ruins be used as a tourist attraction to show the cruel and humbling power of nature.

When the bridge blew down, most people feared it was the death-knell for tourism in the area. But in a fit of “never say die,” reinventing the remaining bridge section as a pedestrian skywalk quickly took shape with the state allocating $700,000 in June 2005 to repair the remaining towers.

DCNR submitted an $8.9 million proposal for a Visitor Center and a Skywalk 600 feet long and 225 feet high featuring an octagon observation deck with glass floor at its center. It would allow visitors to stroll out on the remaining support towers high above the valley floor with a breathtaking view.

The lifeless remains of the toppled towers would stay put in the valley below for viewing from the new observation deck. A hiking trail through the valley would give visitors a close-up view of the tornado’s destruction.

Image: The Kinzua Skywalk – Photo by Tom Huntoon

Construction of the new Skywalk and Visitor Center began in the fall of 2009. The six towers that remained standing were reinforced, new bridge decking with ramps and railings were installed. DCNR was quick to assure “skywalkers” that the walkway would be routinely inspected to ensure their safety.

At Long Last, the Skywalk Opens

Costing $4.3 million the Skywalk opened to the public on September 15, 2011 with the DCNR predicting a handsome return on the investment — $11.5 million annually in tourism revenue for the region.

DCNR Secretary Richard J. Allan welcomed visitors to a new experience at Kinzua Bridge State Park. “Eight years after the historic railroad viaduct at Kinzua Bridge State Park was damaged by a tornado, visitors can experience, in a new way, what the structure once was, and also understand the power of the forces of nature that claimed a portion of it,” Allan said.

“Understanding that this is an important tourist attraction in McKean County, DCNR felt it was important to continue to tell the story of its history, construction and destruction and to invest in this signature destination within the Pennsylvania Wilds region,” Allan said.

Equally as stunning as the Skywalk itself is the adjacent 2,800 square-foot Kinzua State Park Visitor Center. Here visitors immerse themselves in an interactive walk-through history in the Center, which includes a lobby, two exhibit halls, a PA Wilds Conservation Shop, park administrative offices, public restrooms and classroom space.

Image: Kinzua State Park entrance

“Since the skywalk at Kinzua Bridge State Park was completed in 2011, we’ve seen a growing number of visitors at the park coming to enjoy this unique experience,” says DCNR Secretary Cindy Adams Dunn. “The new center enhances their visit, welcoming them with exhibits and information about the history of the area and the many opportunities for outdoor activities at the park and in the Pennsylvania Wilds region.”

Image: Skywalk and State Park Visitors Center – photo by Tom Huntoon

Kinzua Bridge State Park is one of DCNR’s key investment areas in the Pennsylvania Wilds, as well as along PA Route 6 heritage corridor and within the Lumber Heritage Region.

Supporting the local artisans and craftspeople is the PA Wilds Conservation Shop. Located at Kinzua Bridge State Park, the Conservation Shop features primarily locally made products that reflect the region’s beauty, bounty, and rural traditions so visitors can take home a piece of the PA Wilds.

Image: Inside the PA Wilds Conservation at Kinzua Bridge State Park – photo by Olivia Blackmore

Kinzua State Park Celebrates 60 Years with More Milestones

Not only is 2023 the 20th anniversary of the Kinzua Bridge tornado disaster, but it is also the 60th anniversary of the park gaining state park status.

In addition to the 60th anniversary of the Kinzua Bridge State Park and the 20th anniversary of the tornado, this year marks the 30th anniversary of the Kinzua Bridge Foundation (KBF). The volunteer foundation is dedicated to the preservation of the Kinzua Bridge, the promotion of its historical and cultural significance, as well as further development of the adjoining state park.

The park area is becoming a favorite destination for hikers as well. The recently completed Mt. Jewett to Kinzua Bridge Trail, a 7.8-mile trek, was selected as Pennsylvania’s 2023 Trail of the Year. The trail is part of the larger Knox & Kane Rail Trail and is a converted rail line used for walking, jogging, biking and horseback riding.

Image: A family on the Knox & Kane Rail Trail

Epilogue

Way up high out on that Skywalk, the wind howling and whistling through the vast Kinzua Creek Valley gives us a true sense of Mother Nature’s power.

The tragic part of the Kinzua Bridge disaster is that repairs being made on the day of the tornado 20 years ago were running ahead of schedule and more than halfway complete. Who knows? If the tornado had hit a few weeks later, the entire Kinzua Bridge might still be standing today.

While most people deem the bridge’s long life a success, others view the bridge collapse as a failure. They say the old 1882 anchor bolts should have been replaced… the bolts could have been replaced… and if they would have been replaced, there’s the likelihood today’s trains would still be crossing General Kane’s “tracks in the sky.”

But how many structural engineers in 1882 could have realized the potential failure of iron anchor bolts in a tornado, having just built something so massive in such a short amount of time and something that would last so long?

The Kinzua Bridge remains an engineering marvel of its era and the reinvented modern-day Skywalk, with that beautiful Visitor Center, serves as a first-class tourist attraction for more than 200,000 thousand tourists every year. The majestic Skywalk is recognized as one of the top 10 skywalks in the world. It is on the list of National Register of Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks and the National Register of Historic Places.

Image: Kinzua Skywalk and Observation Platform – photo by Tom Huntoon

So, we come here often to bask in its boundless beauty, ponder the power of Mother Nature and witness her wrath.

And we leave, fully aware that Mother Nature always wins.

Related Articles

New sculpture made of recycled bicycles makes a splash along rail trail in Kane

Read MoreSeptember in the PA Wilds – a new beginning

Read MoreWhy Pennsylvania’s fall foliage season is the most beautiful

Read More