Henry Shoemaker and the Lost Chord

I’m sure when my editor asked me to write a Valentine’s article for the PA Wilds Are Calling blog, she was thinking of something different. It’s certain that she expected “Six Romantic Getaways in the Pennsylvania Wilds” or “Romantic Bed and Breakfasts To Take Your Valentine To” or something like that. But that kind of thing just isn’t in my wheelhouse. I’ve never been a very romantic sort of guy, and my wife and I have a kindergartener. It’ll be 2036 before we can manage any sort of romantic getaway.

Fortunately, Henry Shoemaker is there for me.

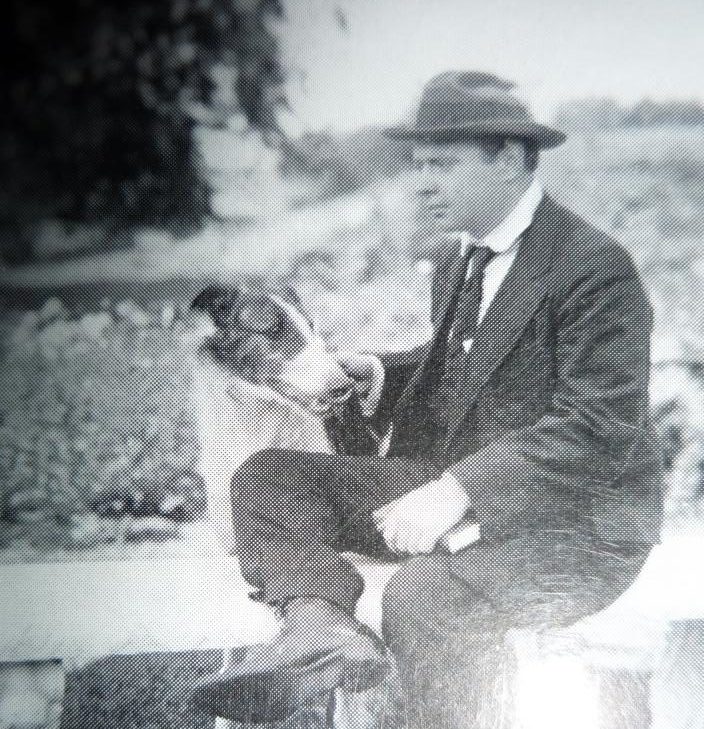

Henry Wharton Shoemaker, Pennsylvania’s only official State Folklorist, lived in Clinton County. He is known for writing down various legends in what is today the Pennsylvania Wilds. Though he’s had his share of detractors, he left us with some excellent stories from the area. And in addition to writing down legends of ghosts and curses, he wrote some romantic stories as well.

(Photo of Henry Shoemaker at right provided by the Ross Library.)

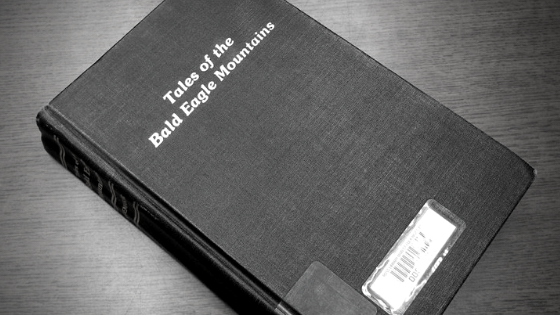

One of these is “The Lost Chord,” from the book “Tales Of The Bald Eagle Mountains.”

The story takes place in the mountains of Beech Creek Township, near the I-80 Frontier. It’s in Clinton County, very near the border of Centre County, and there are some excellent hiking trails near there, in case you might want to take your Valentine for a hike.

According to the legend, there was a young man living in a cabin up there who was a talented musician. Shoemaker stated that he’d gone for a meeting with the young man, and noticed a small sculpture on the piano. Shoemaker describes it as “A young girl, with coal black hair, wearing a hat of dark blue, with a black wing in it, clad in a basque costume of electric blue, carrying a wand in one of her pretty white hands.”

The young man told the story of how he’d acquired the sculpture.

Three years previously, the young man had been traveling from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh by train. He saw one of his fellow passengers, a young woman, looking out the window. When she turned, he realized that she was the most beautiful woman he’d ever seen.

It was what you’d call love at first sight.

“I felt as if I knew that young woman,” the musician said. “I could love her as no woman had been loved before… if I but had the privilege of her acquaintance.”

And then, having had that thought, the young musician was too shy to speak to her, and watched in silence as she got off the train near Harrisburg.

Hey. We’ve all been there.

So the young man decided to find the woman. He began to ride the same train line frequently, hoping to see her again. Comparing the situation to music, he said,”Spiritual love ought to come from harmony, two or more different musical sounds produced simultaneously.” He felt that he was playing one chord of this lost love, and that he would be complete if he could find the other one, the lost chord in this harmony.

One day, while searching, depressed and despondent, the man stopped at a local shop. He saw the porcelain statuette in the window, looking exactly like his lost love. The store owner had no information on who had made the little sculpture or where it had come from, but the young man bought it and took it home, believing it to have been modeled after the woman.

He took it home, set it on his piano, and sat down to play. “When I struck the first notes, to my surprise and infinite delight,” he said, ”the porcelain statue began moving towards me, tripping lightly and in perfect time with the music. It was in harmony with my instrument, with me.”

From that moment on, whenever he played the piano, the statuette would move, and he believed it to be moving toward wherever his lost love was in the world.

The young man would play, and know that his love was out there somewhere, waiting to be found. Waiting with hope. And Shoemaker watched him play, and wrote the story down, documenting for the future the magic of a lost love in the mountains, waiting to be found again.