Grandpa’s woodhick days came to an end with the lumber boom’s last gasps around 1918. His boyhood homeland was bare, stripped clean of timber: a landscape in ruin, ravaged by erosion and wildfires.

As a 10-year-old boy, I found it hard to believe that these mountains could ever have been anything but green and beautiful, exactly the way our forefathers found them. I couldn’t get enough ‘history’ as to how we made the journey from ruin to recovery.

Change Was Coming – And It Was Wielding an Axe

As the early settlers pressed inland from the east coast, the demand for lumber soared. Treaties with the Native American tribes opened more land, and the hills came alive with the sound of axes and crosscut saws.

Thousands of acres of enormous old-growth trees came thundering to the ground. Homes and farms sprang up all across the Wilds. So did many little towns. A prime example is Cross Fork in Southern Potter County. Almost overnight, Cross Fork exploded from a population of practically zero to a population of several thousand people!

Timber was harvested for all sorts of things, not just for homes. Tall and straight, majestic 100-foot-tall white pines were used for the masts of clipper sailing ships. Our timber went into making the Conestoga wagons, bound for the wild west. Hemlock was used to create leather, making Pennsylvania a world leader in leather production by the 1890s. Our timber fed the industrial revolution’s iron-ore furnaces and played a key role in building America.

Up in the mountains and down through the hollows, lumberjacks were hard at work, putting in 12-hour days. Their lumber camps were mostly nothing more than cold, dank, drafty shanties.

“The work was demanding and dangerous; the work sites and housing were unsanitary and unsavory. The changes the newly industrialized logging business wrought were immensely important to the nation’s growth and were fantastically—and tragically—transformative of the landscape.”

– Woodhicks and Bark Peelers”- (Penn State University Press)

Winters were brutal, but winter is the prime time of year for mountain timbering ‘made easy’. In August and early autumn, trees were felled and cut into logs of varying lengths. With the first snows, the logs were dragged onto sleds and slid down the steep hillsides. The logs were then pushed into small streams below, floated down to larger streams and rivers, or built into rafts for floating to their final destinations.

The North and West Branches of the Susquehanna, Allegheny, and Tioga Rivers were teeming with timber as our waters became logging superhighways. Railroads came later, making their way into hard-to-reach mountain forests and bringing more lumber to market.

Across the PA Wilds in the 1800s, lumber was plentiful and, in the annals of our lumber history, nothing in the nation matched the ingenuity of the massive “Williamsport Boom,” a seven-mile-long stretch of man-made stone ‘crib’ islands and chained logs erected in the Susquehanna River in Williamsport.

The boom acted as a huge ‘net’ designed to catch and hold floating timber until it could be processed at one of the nearly 60 sawmills. There were so many logs packed into the boom that you could walk across them from one side of the Susquehanna to the other, more than 300 million board feet of lumber! You can still see remnants of the boom cribs on the river today.

Who Says Money Doesn’t Grow on Trees?

In the 1870s Williamsport became known as the “Lumber Capital of the World,” with many men making their fortunes.

Williamsport’s East Fourth Street was home to more millionaires per capita than anywhere in the United States, and the street became known as “Millionaires Row.”

Most of those stately old mansions that lumber built still line East Fourth Street today, and you can take a guided-walking tour. The Taber Museum in Williamsport is home to a treasure-trove of lumber industry history and heritage. Even Williamsport’s minor league baseball team, “The Crosscutters,” gives a nod to the city’s rich lumber history.

“The forest products industry in the early 20th century was extremely profitable for many in the region,” explains Holly Komonczi, LHR Executive Director, “so much so, that the hillsides were stripped bare. Many people found extreme wealth and many people worked sun-up to sundown just to support their families, men, women and children among them.”

A recent LHR diversity study gives accounts of women, not only owning and running lumber camps, but doing the hard work, too. “Women also used crosscut saws, loaded logs on trucks and drove them to market, prepared and served meals to men,” said Holly “The women who worked at lumber camps were up before the workers and slept after tending to the meals and to the children who accompanied them at the camps.”

Downstream in Williamsport, the “boom” became a “bust” when the world-famous boom collapsed, sending hundreds of millions of board feet of lumber down the Susquehanna and, with it, Williamsport’s “lumber capital” status. In 1907, the Susquehanna Boom Company disbanded and, tragically, what was left all across the region was an ecological disaster.

“There are few places in the East where the natural beauties of mountain scenery and the natural resources of timber lands have been destroyed to the extent that has taken place in northern Pennsylvania.”

– The U.S. Geological Survey, 1900.

By 1900, our beautiful mountains were barren and ugly. An estimated 350,000 acres per year were decimated by erosion and wildfires that ripped through stumps and scrub brush. The PA Wilds became known as ‘the Pennsylvania Desert.”

Change Comes Again with a Sense of Sustainability

Born out of sheer necessity, a major change was coming to these mountains in the 1920s. But it was no longer a matter of felling trees and moving them to market; it was a matter of how to protect the precious remaining few forests and how to restore millions of blackened acres.

This slowly gave rise to a conservation and sustainability ethic, said the LHR’s Holly Komonczi. “The rebirth of the forests was a team effort. The Pennsylvania Division of Forestry was first led by Joseph Rothrock, “the father of forestry.” He recognized the need to keep the forests healthy and properly managed.”

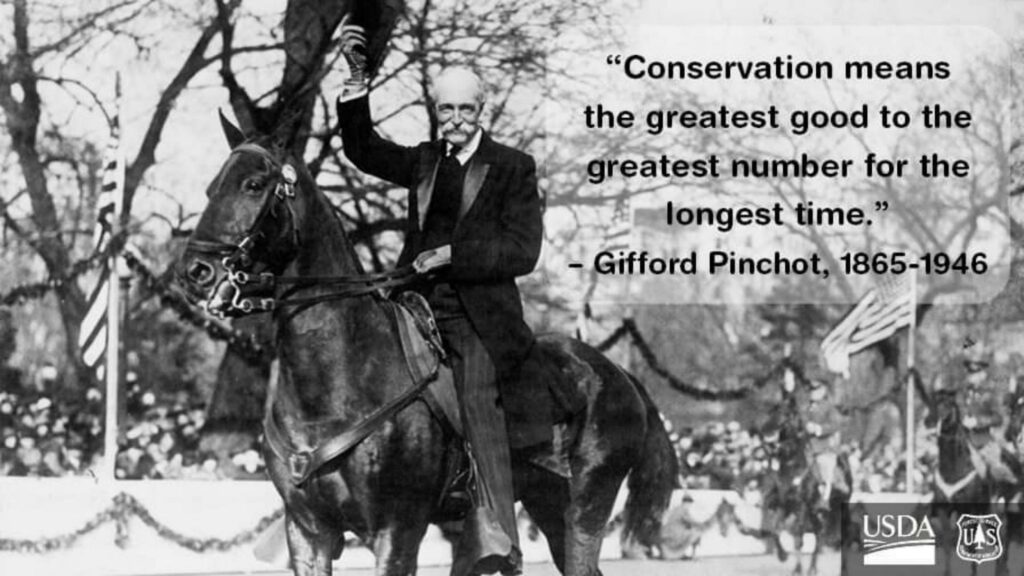

Others followed Rothrock’s lead. Among them was Gifford Pinchot, Chief Forester for the Division of Forestry. Pinchot later became a two-term Pennsylvania Governor and set up work programs across the state. These became the model for President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), fueled by the stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression.

To put people back to work and jump-start the economy, Roosevelt launched the CCC public works program, which later became known as “Roosevelt’s Tree Army” due to the millions of trees planted. Young recruits became known as “The CCC Boys.” They built our trails, dams, fire towers and shelters in the state’s forests and our present-day State Park system.

“FDR’s CCC initiative helped us regain our beautiful forests,” explained the LHR’s Komonczi. “There were a multitude of CCC camps in the Lumber Heritage Region and all provided most of the recreational areas you see today.”

By the end of the CCC program an estimated 50,000,000 trees were planted across the commonwealth and more than 6,300 miles of roads and trails were built through the mountains.

We Have More Wilds Today Than 100 Years Ago!

Today, our forest products are in demand throughout the world, and our modern lumbering practices ensure that the forest will be properly managed.

“Pennsylvania currently leads the nation in total hardwood lumber production,” said Joshua Roth, Executive Director of the Pennsylvania Lumber Museum, located on Scenic Route 6 between Coudersport and Galeton in the Pennsylvania Wilds’ Dark Skies Landscape. “We rely on the forest for so much; forest product industries generate over $21.5 billion in annual direct economic impact and employ more than 65,000 Pennsylvanians”

As the history of the Pennsylvania lumber industry is recorded at the Museum, the work of the museum is still unfolding. “With the support of our community,” explains Joshua, “I am hopeful that the PA Lumber Museum will be here to document and preserve the history of PA’s lumber industry and forests and, with our modern sustainable management practices, that will hopefully be for a very long time.”

We’re not done yet. A Charity Checkout for Conservation available at the PA Wilds Conservation Shops at Kinzua Bridge State Park and Leonard Harrison State Park, as well as the online PA Wilds Marketplace, allows you to make donations to support PA Wilds parks and forests. Those funds are earmarked for reinvestment back into our state parks and forests across the PA Wilds region.

Today’s sustainability practices have resulted in a bountiful mix of timber, and Pennsylvania has more forests today than it did 100 years ago! This is a story of true survival because after 100 years of stewardship we are now one of the largest blocks of green between NYC and Chicago.

Looking back on our lumber heritage, we have much to be proud of, because our Pennsylvania Wilds forests contributed mightily to the building and shaping of these United States of America.