Every year around mid-August, millions of monarch butterflies take flight from their botanical homes and travel thousands of miles along an ancestral fall migration path.

Monarchs in the eastern United States, including monarchs that call the Pennsylvania Wilds home, depart to Mexico to overwinter together in fluttering clusters, only to return to our wildflower fields and backyard gardens in the spring.

Every year around mid-August, millions of children across Pennsylvania take a similar migratory path, departing from their sunsoaked backyards and the ease of summer vacation and into large yellow buses that trace familiar routes to their primary and secondary schools. There they will nest together through autumn and winter in chattering clusters, before returning for more backyard adventures in the spring.

That is the dissonance of September for families who love to be outdoors. In our neck of the woods, on any given day, the weather is likely to be as nice as August – as hot and mild with clear blue skies and soft green grass – but despite astronomical evidence to the contrary, in our culture, summer ends when the kids return to school.

For many families, the outdoors become something viewed only through their windows or, worse, their screens.

So one morning just after the start of the school year, when I asked my two Wilds boys if they wanted to take an adventure with me to one of our favorite PA Wilds spots, Parker Dam State Park, they looked at me confused.

“Are we going to swim?” my six-year-old asked, his backpack and school sneakers on the floor beside him.

“Well no,” I explained hesitantly. “The swimming beach closes at the start of September. But there are other things to do there!”

The boys looked dubious. We had spent many summer days at Parker Dam in their short life, but almost every hour had been dedicated to the soft sand beach and cool, freshwater lake.

While we took occasional breaks to the concession stand to munch on salty, crinkle-cut fries and enormous ice cream cones that dripped down our sunscreen-soaked arms, we seldom journeyed much further. The beach and the lake were simply nice enough to entertain a family for the entire day, no other attractions required.

Established in 1936 as a Civilian Conservation Corp effort, Parker Dam State Park is now a bustling, busy park that enjoys thousands of visitors each year. Its 968 acres boast numerous hiking and biking trails, dense thick conifer forests, premier camping spots, and the crown jewel for local families – a sparkling, man-made lake created by the damming of Laurel Run.

On any given summer day, the beach is filled with families basking in the sun, building in the sand, and splashing and laughing in the lake. I’ve been swimming at Parker Dam since I was a toddler, and some of my favorite childhood memories happened on its wooded shores.

Since then, I’ve strived to instill a similar love with my children. They’ve been frequenting the park since they were in diapers, and it’s their favorite spot for adventure in the summer as well.

On the sunny September Sunday, the park was just as beautiful as summer, the tips of the trees beginning to grow auburn in the waning season. Each pavilion was still filled with families picnicking, the lake still had several kayakers floating leisurely by. We passed numerous hikers as we walked, and the campsites were still full.

At the bottom end of the lake, where the water is dammed, there is a small, wide waterfall with a spillway. The easiest way to get from one side of the lake to the other is to walk across the large rocks beneath the waterfall, though careful footing is required, lest one end up with a wet boot or, worse, a twisted ankle.

My boys loved running across the rocks, configuring different paths as they bounded away from me. “Careful feet!” I shouted, uselessly. They weren’t listening. And, frankly, they no longer needed the reminder.

As I watched them leap from rock to rock, I marveled at how big they had grown – how my six-year-old, now in his first year of kindergarten, dashed ahead confidently, no longer looking back to see if I was right behind. My four-year-old, in his first year of preschool, stumbled, gently scraped his knee, surveyed the damage dispassionately, and returned to his play unbothered – no big tears, no boo-boo kiss from mom required.

They ran ahead of me, up over the bank to the other side of the lake and then, ahead, through a trail that wove through the hillside forest that overlooks Parker Lake.

“Not so far ahead!” I shouted, aware that up until this year, both boys had clung to me whenever we went hiking, keen to avoid danger.

Now I struggled to keep up with them, catching glimpses of them running through the thick undergrowth and brief shrieks of laughter as they scaled large rocks and jumped over tangles of roots.

We emerged off the Laurel Trail near the campground bridge and followed the road back to the recreation area. There we found a small wildflower garden surrounded by a wooden fence.

“It’s a butterfly habitat,” I started to explain, but my oldest son cut me off.

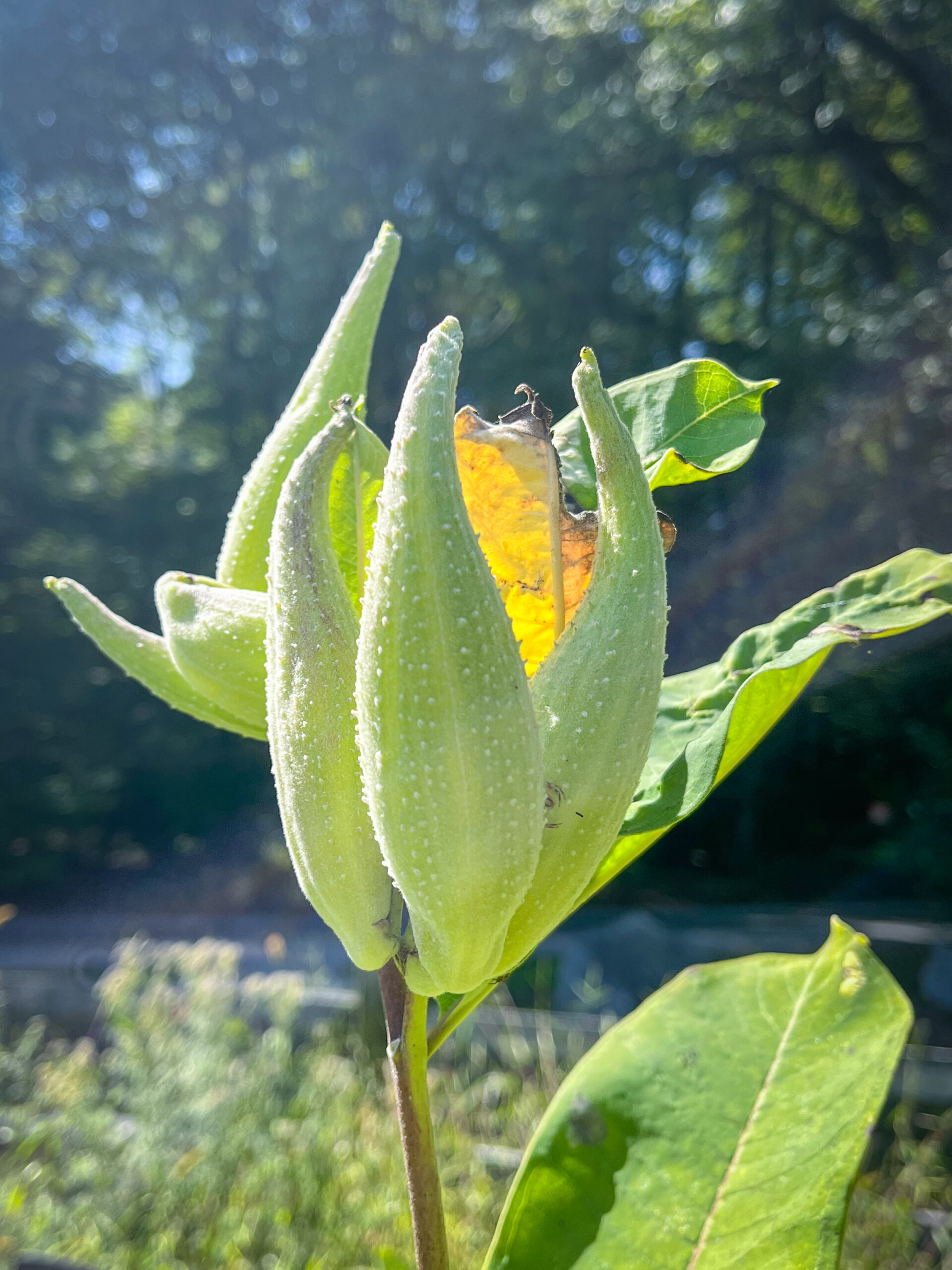

“That’s milkweed,” he explained, pointing to a tall, broad-leafed plant with spiny, green pods. The clusters of flowers, ordinarily vibrant in shades of pink and white, were already dried in the end-of-summer sun. “That’s what monarch butterflies like to eat.”

I raised my eyebrows at him. “That’s right,” I said, surprised. “How did you know that?”

“We learned it at school,” he replied, shrugging.

It’s true that milkweed, a perennial plant native to Pennsylvania, and monarch butterflies have a special relationship. Monarchs only lay eggs on common milkweed and monarch caterpillars only eat milkweed leaves. As an entire monarch migration takes three to four generations of butterflies to complete the cycle, monarchs rely on ample access to milkweed along the way in order to complete the trek.

Declining natural habitats combined with widespread pesticide use has decimated milkweed and we are seeing the impact on monarch butterfly populations, which are declining, along with other pollinators, at record numbers. Pollinator habitats, like the one found at Parker Dam, are part of the important work PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) has been doing to educate the public and help reverse diminishing pollinator populations.

My boys spent a while at the butterfly garden, smelling the aster flowers and admiring the strangeness of a milkweed pod. “There aren’t any butterflies here,” my four-year-old pouted after a while.

“Maybe they’re already on their way to Mexico,” his big brother replied wisely.

I thought about the lifecycle of the monarch – how brief, how beautiful, and how dependent upon the wisdom of their ancestors they are. Monarch butterflies typically arrive in the PA Wilds in May to breed and lay eggs, but those particular butterflies don’t make the journey back to Mexico in the fall. By then they have died and their grandchildren – or great-grandchildren – complete the journey for them.

And I thought about my two little Wilds children – the ones who ran ahead of me, who knew the best way to navigate river rocks, who were already beginning to teach others the knowledge that they had learned.

And I thought about the places in the PA Wilds that raised me and how they were places of refuge now for my children as well – places to host them and nourish them as they embark on their own journeys.

About the Series:

The Wilds Child: Exploring the PA Wilds with Little Adventurers is a series that features stories, travel tips, landscape recommendations, and the occasional piece of unsolicited parenting advice. Whether you’re a family in town for a visit or a local looking to show their own children your region’s rich heritage, let local writer, community organizer, and fellow-parent, Tia DeShong, help you plan your next adventure in the PA Wilds.