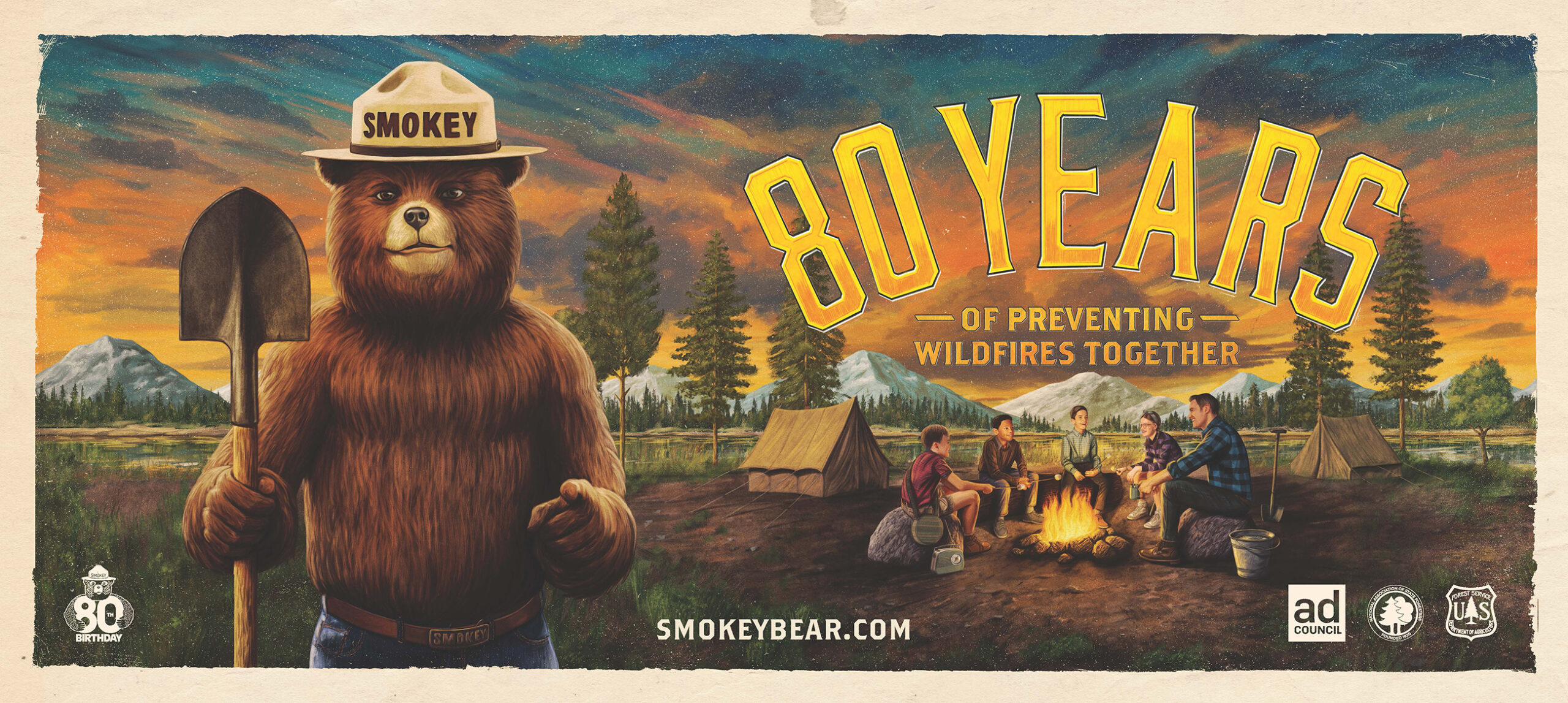

Smokey Bear turned 80 years old!

By Jim Hyland

All photos courtesy of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service.

If you think you’re getting old, look no further than our beloved Smokey Bear for affirmation.

On August 9th, 2024, Smokey turned 80 years old! So to recognize his birthday, I thought I’d recount his distinguished career and update his enduring message during this year of extreme wildfire behavior and unprecedented warm temperatures. If you were born after 1940 or so, Smokey Bear has been around as long as you can remember. Whether you first saw him strutting in a parade, campaigning on TV, or posing for one of his many posters, Smokey has had a full life campaigning against the dangers of wildfire.

Let’s take a look at his most interesting story:

In 1937, just seven years before Smokey Bear was born, the country’s first anti-wildfire campaign was initiated. At that time, about forty million acres of forestland were being lost to human-caused fires annually. President Roosevelt decided to do something about it.

He called upon the fictional “Uncle Sam” to help him. Uncle Sam was the image of an old-aged, stern-faced, patriotic man who represented the United States, and whose image was popular on WW1 era “I Want You” recruiting posters. Uncle Sam traded his red, white and blue duds for forest green and showed up on posters as a ticked-off forest ranger. He exclaimed: “Your Forests, Your Fault, Your Loss!” while pointing at a raging forest fire.

In the spring of 1942, following the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, Uncle Sam’s forest fire campaign was rekindled by way of a remarkable series of events. Here’s what happened: A Japanese submarine was able to sneak into US Pacific coastal waters and surfaced off the coast of Santa Barbara, California. The submarine then fired on and set aflame an American oil field close to the Los Padres National Forest, thus threatening thousands of acres of virgin timber. Americans were shocked that the US mainland had been attacked, and feared that the Japanese would set the great forest resource of the coastal Northwest on fire. But they didn’t know the whole story. The Japanese were already plotting.

Egged on by Lt. Colonel Jimmy Doolittle’s April 1942 air raids on Japanese Islands, the Japanese began releasing the first of more than 9,000 incendiary balloons into the high altitude “jet stream” winds over Japan.

The balloons were thirty-two feet in diameter, and were filled with 19,000 cubic feet of highly flammable hydrogen. They were supposed to travel across the Pacific, and using a too-complicated system complete with altimeters and sandbags, they would explode on the US mainland. It is estimated that about a thousand actually made it here, and although they were mostly “duds,” they did not go unnoticed by the US military. In order to prevent widespread panic, and to “deflate” the Japanese military ego, the strategy was to “cover up” the attacks.

The Japanese would not be able to tell if the balloons were working or not if Americans deployed radio silence. The media were hearing reports of the balloons, but they dutifully obeyed their order for quiet. Thankfully, the balloons proved to be ineffective and the strategy paid off, that is, until

1945, when a group of kids found one in the Oregon woods and unknowingly tried to move it. The balloon exploded and a woman and five children were killed. They were the only people to die on the American mainland as a direct result of foreign aggression. And so with its Japanese incendiary balloon secret, and with millions of American men fighting overseas, including former forest firefighters and managers, the US Government was again stressing the importance of keeping fire out of our forests… preventing forest fires was now a way for Americans to help win the war. Disney’s “Bambi” appeared in 1944 and, as all deer hunters know, was very successful in raising public sentiment about both hunting and forest fires.

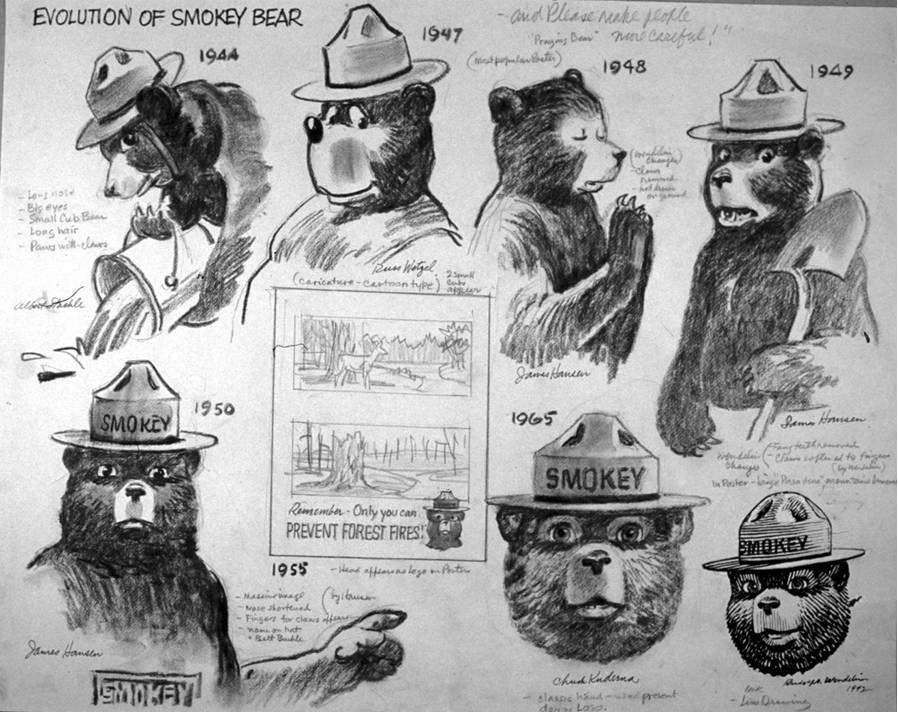

The US Forest Service asked to borrow Bambi for a year, and then decided to create their own cute animal figure to promote the cause. They chose a bear.

Smokey was named after a popular NYC fireman named Smokey Joe Martin, and at first was a little cuter than today’s “fatherly” Smokey. He debuted on August 9th, 1944, and lives on as one of the most successful ad campaigns in our history. A few years later, in 1950, a real black bear cub was rescued from a human-caused forest fire in New Mexico.

He was named Smokey after the fictional national symbol, and he eventually ended up in the National Zoo in Washington DC. He was the most popular attraction for almost 25 years. He died and was buried near his home in Capitan, New Mexico in 1976.

Since Smokey’s debut, human-caused wildfires have been reduced by half, even though ten times as many people use public forests as they did in the 1940s. Here in Pennsylvania, the months of March, April, and May are prime wildfire season. In fact, 83% of all wildfires in Pennsylvania occur in these three months.

But why? Shouldn’t the hottest months, like July and August, be the most fire-prone? The potential for fire in the spring months has to do with several factors: the lack of a shady leaf canopy in the forest, the general absence of greened-up foliage in the understory, the strength of the sun, the presence of strong, dry winds, and the tendency for people to want to clean up (using fire) around their homes after the winter. The same combination also occurs briefly in the fall when the leaves drop October through early December, but the window of opportunity is not usually open as long. Today Smokey is facing a dilemma.

In recent years scientists and professional land managers have begun to realize that both naturally and artificially occurring, low-intensity fires (aka prescribed) can be beneficial to forest ecosystems. However, the concern is that the forest, in its present condition (lots of woody debris via lack of low-intensity fire), and under the right weather conditions, will burn with a high, uncontrollable intensity whether we like it or not. Contributing to the problem, people continue to build their homes in the woods. Add in the climate change-related extreme temperatures and drought in fire-prone regions of the United States, and we have a situation where it’s more important than ever to remember Smokey’s words… Only You!

About the author, Jim Hyland:

Jim Hyland worked his entire career as a DCNR forester in the beautiful north central region of the state. There, he forged a strong appreciation of the people and the woodlands they value and enjoy. Most recently, he was the district forester in the Tioga State Forest, headquartered in Wellsboro, Tioga County. He retired in October 2023. A native of Shenandoah, Schuylkill County, Hyland started his career with the Bureau of Forestry as a Penn State University intern in the Rothrock State Forest District, Centre County. After college, he began working as a forester in Tiadaghton State Forest District, Lycoming County. He was later promoted to Tiadaghton Assistant District Manager and spent two years directing state forest maintenance and recreational programs in the district. Hyland has also served as a Forest Program Specialist with the Bureau’s Division of Operations and Recreation, with emphasis on the Pennsylvania Wilds Region. He was active with the Bureau’s History Committee, and with a love of writing has penned many articles for local newspapers and DCNR publications documenting the lore of north central Pennsylvania and his native coal region, among other topics. Also, he has served as a firefighter and public information officer on many firefighting assignments in the Western U.S. As head of one of 20 state forest districts across the state, Hyland oversaw forest- growth management, personnel coordination, infrastructure maintenance, recreation, and fire prevention and suppression. He also managed service foresters who provide support, direction and technical assistance to private forest landowners. Hyland holds a bachelor’s degree in Forest Management from The Pennsylvania State University. An avid outdoorsman, Hyland enjoys nature writing, woodworking, history, backcountry canoeing and hiking, hunting, fishing, and any type of adventure. Parents of three grown children, he and his wife, Sherry, reside in rural Lycoming County with their Labrador, Finnegan, as well as Ralphie, the calico cat and Kaiser, the African gray parrot.