In the PA Wilds,1816 was known as a year without a summer

As I write this, the Pennsylvania Wilds is just exiting a cold spell. In December, several feet of snow fell on us, and as January comes to a close, the temperature is dropping into the twenties. As cold and unpleasant as this is, at least I know it’ll be over soon. Spring will arrive, the weather will warm up, and I’ll enjoy getting outside again. This is more than the people of Pennsylvania could say back in 1816, when winter came and didn’t leave for quite some time.

Volcanic ash from an eruption elsewhere covered the atmosphere, dimming the sun. This caused a long-term cooling of temperatures worldwide, making it much colder throughout the year than it should have ever been. Water stayed frozen well into June. Crops refused to grow. Throughout April and into late May, feet of snow were still falling on the present-day Pennsylvania Wilds.

1816 was referred to as “The Summer That Never Was,” “The Year Without A Summer,” and “1800 and Froze To Death.”

The Lancaster Land Company had, a couple of years before, purchased over a hundred thousand acres of land with the intent of subdividing them and selling them off. Though the plan looked good on paper, the ongoing winter made it a bad investment, with people losing interest in relocating or establishing farms.

The land wound up being sold for back taxes. “Soon a great portion of them were in the tax market, sold and resold many times for unpaid taxes, for thirty years and upward,” states the book “History of Warren County.”

Over in Potter County, several families were relocating near Coudersport on March 1, 1816. The families of John Dingman, Abram Dingman, and Nathan Turner were traveling north with a wagon. The weather was described as “cold and wintry,” and the wagon became snowbound as they got closer. Unable to proceed, they stopped the wagon.

Turner and his wife elected to stay and guard the wagon, while the rest of the party went for help. Three of the women got on horses, and they headed out. Unfortunately, they hadn’t found anyone by nightfall, and they chose to stop and camp out overnight for fear of getting lost.

One of them took some wood from a dead hemlock tree and started a fire by shooting a musket into it. This kept the family warm enough until morning, at which point a search party came and rescued them.

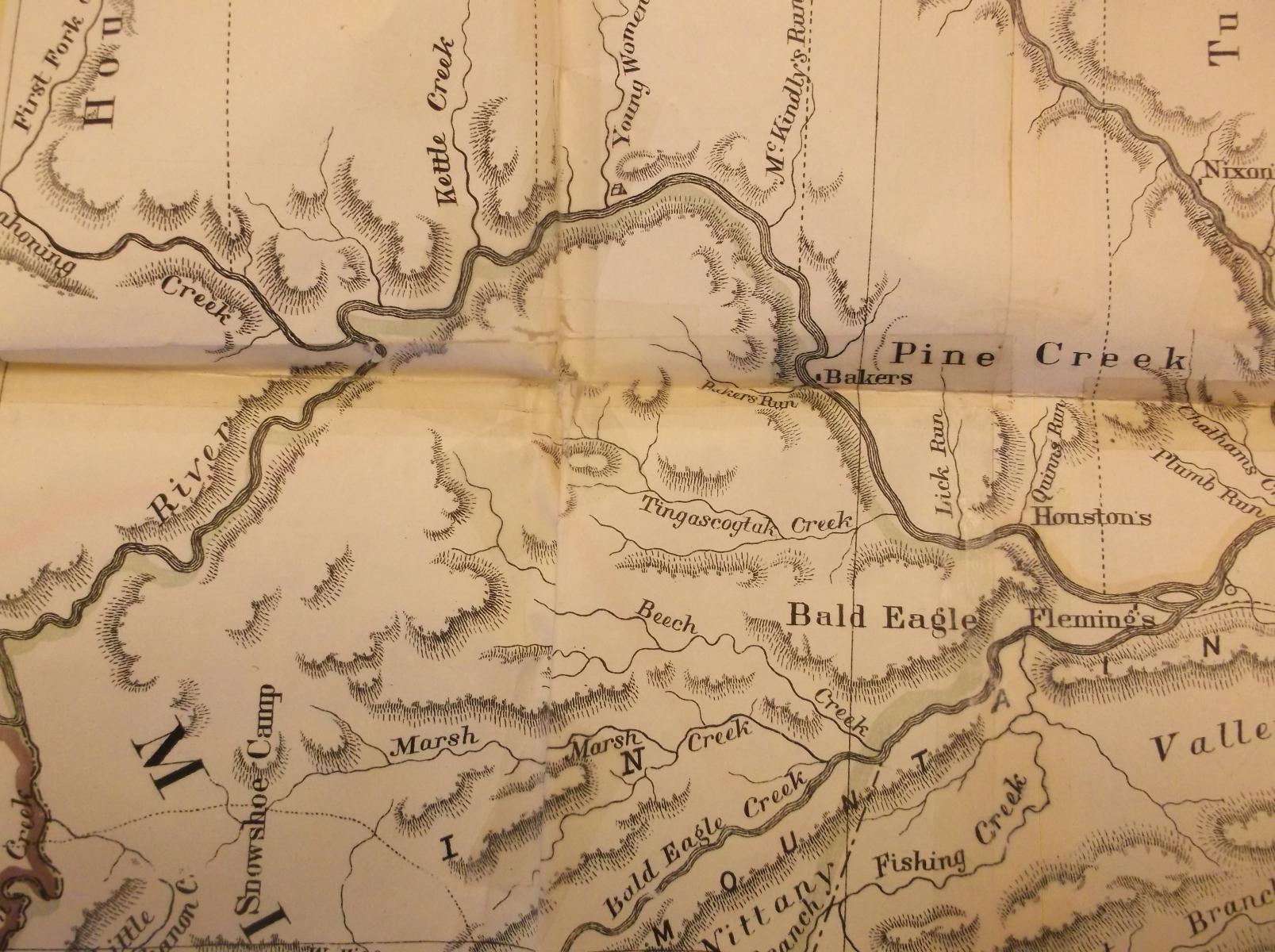

In northern Clinton County, Simeon Pfoutz and his family were struggling to keep their farm going. The ice on Kettle Creek didn’t melt until mid-April, and then more snow came. Pfoutz was unable to grow crops, with the exception of a little bit of hay, which was gone fairly quickly.

By hunting and fishing, he was able to feed his family just enough to survive. His wife made gloves for everyone out of the hides Pfoutz hunted. The pigs, which will eat anything, were given leftover fish. Both the pigs and the cows began eating birch bark from fallen trees, and took to following Pfoutz around every time he left the cabin carrying his axe, in the hope he’d cut down a tree for them.

By the spring of 1817, the weather had begun to clear, and the next summer returned to normal. Interestingly, I went through many old cemetery records and discovered evidence that we’re pretty tough, here in the Pennsylvania Wilds: There doesn’t seem to have been an increase in deaths during that long winter. Most of the people here survived.

I did find something else, however. There was definitely an upswing in births from late 1816 onward; Many people were born that winter and immediately afterward. Draw your own conclusions.