Fossil Fri-YAY! – The Brachiopod

By Jamie Withers

The most common fossils found in Pennsylvania are of the phylum Brachiopoda, coming from the Greek “brachion” meaning ‘arm’ and “podus” meaning ‘foot’, and better known as brachiopods (BRAK-ee-oh-pods). These marine invertebrates were among the first in the Earth’s oceans during the Cambrian period, 550 million years ago. They reigned as the most common shelled marine invertebrates on the planet for the next 300 million years during the Paleozoic (meaning “ancient life”) Era, which ended with the Permian Extinction just before the rise of the dinosaurs. During the Paleozoic, brachiopods were commonly found in warm, shallow waters – indicating that Pennsylvania was underwater at least once during the geologic past. The prolific presence of brachiopod fossils during the Paleozoic Era makes them a great index fossil, meaning that they help paleontologists and paleoecologists learn about the age of the rocks, the marine environment at that time, and other critters present in the same location and period.

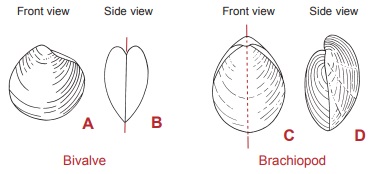

Brachiopods are similar to clams (bivalves, or two-shelled), except that the top and bottom shells of brachiopods are not identical, though the shells have symmetry when viewed from the top (“front” view below) and bottom, and along the edges from the front and rear shell seams.

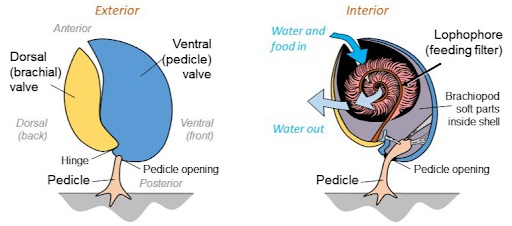

Inside their shell, strong muscles held the valves together to protect the critter’s soft body. Some brachiopods burrowed into the muddy sea floor while others attached themselves to rocks or other objects by a fleshy stalk called a pedicle. As filter feeders, brachiopods acted as the ocean’s vacuum, by filtering the water through a unique organ called a lophophore, to capture edible particles and organic matter.

Image: The side view difference between a bivalve’s identical shells compared to a brachiopod’s. (Hoskins, D.M.)

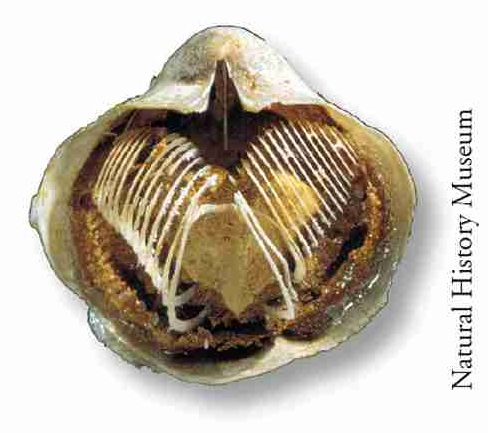

Often well-preserved after their demise, shells are found pressed together but the soft, fleshy parts don’t usually stand the test of time. In rare circumstances the soft flesh can become lithified, or preserved as rock, when chemicals in the watery burial environment replace the rotting flesh.

Image: Brachiopod anatomy (©Kentucky Geological Survey, University of Kentucky)

Brachiopods are still around today, but in much smaller numbers and preferring marine environments that are cold and deep, thus hidden from most people’s discovery. Most of us will encounter the brachiopod through finding fossils of their ancient relatives in sedimentary rocks throughout Pennsylvania, especially in the Catskill and Mahantango Formations. The shells, already composed of hard minerals when the animals were alive, break down slowly over time and were either replaced with more durable minerals left behind by groundwaters, or the impression of the shell was stamped forever into sediment that turned to stone.

Image: Lithification preserved the structure of this ancient brachiopod’s filtration system, the coiled lophophore. (Natural History Museum)

The Mahantango Formation contains significant quantities of brachiopod fossils and those of other prehistoric marine critters such as the trilobite (Phacops rana), our state fossil. There is an exposed collection site in Swatara State Park, along the Bear Hole Trail (Swatara_State_Park_Guide&Map).

Image: Brachiopod fossils in sandstone. (J. Withers, from David Danko’s collection)

Sources

Hoskins, D.M., 1999, Common fossils of Pennsylvania (2nd ed.): Pennsylvania Geological Survey, 4th ser., Educational Series 2, 18p.

www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/brachiopoda

Brachiopods, Fossils, Kentucky Geological Survey, University of Kentucky (uky.edu)

About the author, Jamie Withers:

Jamie Withers is a Senior Geoscientist in the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Forestry. She possesses an undergraduate degree in both Geology and Education, and a Masters of Education from St. Lawrence University in Canton, NY. Prior to joining the Bureau of Forestry she taught Earth & Space Science, Chemistry, and Environmental Science for 14 years. Jamie and her family live in Selinsgrove. In her free time, she enjoys spending time with her family, crafts, reading, traveling, and is a loudly cheering hockey mom.