Earth Day and The Wilderness Act: Deep Roots in the Pennsylvania Wilds

It’s Earth Day’s birthday.

It was 50 years ago, April 22, 1970, that our annual observance of Earth Day began with 20 million people demanding change for a cleaner, healthier, sustainable environment.

A growing number of Americans felt it couldn’t have come a moment too soon.

Many of our rivers and streams were being used as sewers and toxic waste dumps. In nearby Ohio, a river caught fire! Industry belched out smoke, blackening the skies. We were consuming vast quantities of unleaded gasoline, yet air pollution was considered “the smell of prosperity.” The pesticide DDT spelled doom for the bald eagle population and other species.

By and large, mainstream America was oblivious to the many environmental time-bombs which posed a direct threat to our health.

A grassroots Earth Day coalition was formed and 50 years later, by way of the Earth Day Network, that first Earth Day is remembered as the beginning of an all-encompassing environmental movement in the United States. Later in the year, the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was created and, finally, there were laws in place to protect our natural resources.

However, there was another environmental movement underway long before that, beginning right here in the Allegheny National Forest and Surrounds, by Tionesta’s Howard Zahniser. He wrote the 1964 National Wilderness Act that directed Congress to establish and protect wilderness areas on national forest land.

Today, Zahniser is regarded as “The Father of the Wilderness Act,” a man who embodied the spirit of the Pennsylvania Wilds, and all things environmental, wild and wonderful. As an environmental visionary, he raised the consciousness of an entire nation as early as the 1950s and 60s, long before Earth Day was created.

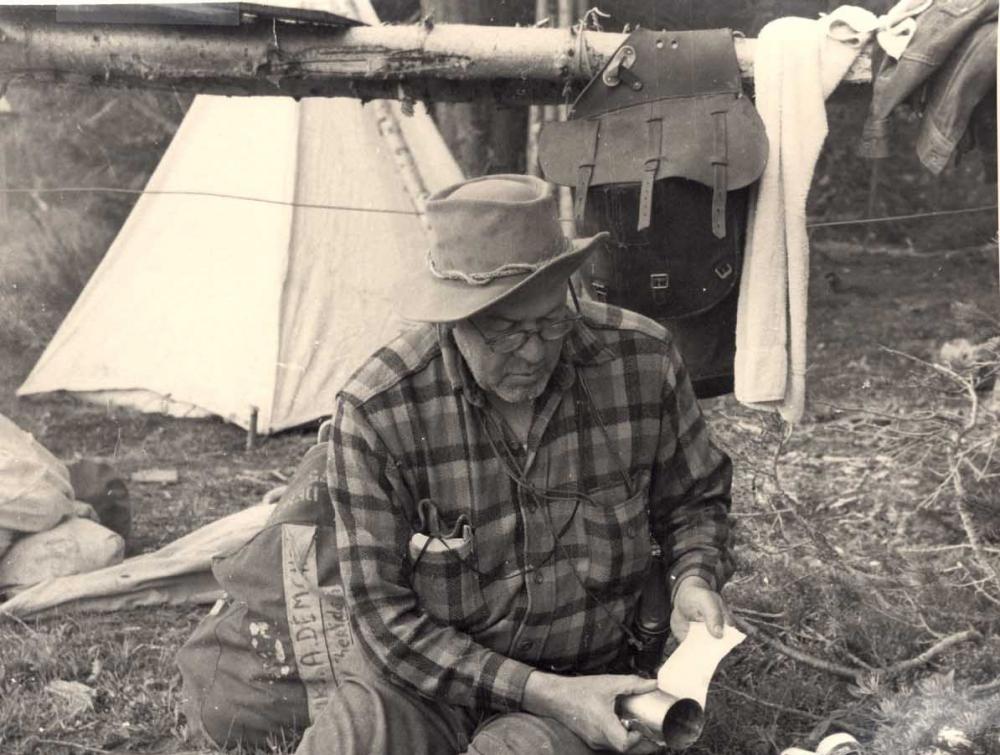

(At right: Howard Zahniser. Courtesy of The Wilderness Society.)

The son of a Free Methodist minister, Zahniser was born in Franklin, Venango County, but grew up in Tionesta, where he fell in love with the mountains, forests and the Allegheny River that flowed near his family’s downtown Tionesta home.

The boy would spend hours wandering the mountain trails, fishing the Allegheny River and the Forest County creeks alongside his neighbors, the loggers and miners.

Even though Howard would later become a fierce critic of certain logging and mining practices, he always maintained an affinity for the workers here in the Wilds, because those jobs put food on the table and provided economic opportunities for many struggling northern Pennsylvania families and communities.

Graduating from Tionesta High School, Zahniser went to Greenville College in Illinois. His first jobs were that of a newspaperman. Returning home from college during the summers, he worked at The Forest Press in Tionesta and later at The Pittsburgh Press. In 1928, he graduated with a degree in English and continued honing his writing skills.

Moving to Washington D.C., Zahniser worked as an editor, writer and broadcaster from 1931 to 1943 with the Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Biological Survey, and its successor agency, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, but he never forgot his Forest County roots. From time to time, he would return to Tionesta, enjoying his love for the area, hiking and canoeing in the Wilds.

He married Alice Hayden in 1936 and together they had four children, Mathias, Esther, Karen and Edward.

In June 1937, Zahniser and Alice set out on a two-week, 100-mile canoe trip down the Allegheny River from Olean, New York, to Tionesta. It was a continuous float trip because the Kinzua Dam hadn’t yet been built. On the final leg of the journey, Howard and Alice camped on Thompson’s Island which, 27 years later, would become part of the 110-million-acre National Wilderness Preservation System that Zahniser’s Wilderness Act later secured in place.

(At right: Howard Zahniser camping in the Wilds. Photo courtesy of The Wilderness Society.)

Along the way Zahniser kept a journal, chronicling their 100-mile long Allegheny River odyssey, which was later turned into a book, Alisonoward, the name of their canoe and a combination of Alison and Howard’s first names

(At right: Zahniser is seen in his canoe, Alisonoward, heading down the Allegheny River. Courtesy of the Howard Zahniser Family.)

Meanwhile back in Washington, he continued exploring opportunities to promote and protect this land he loved and the hard-working people of Forest County, the loggers, the miners, his former neighbors.

From September 1945 to May 1964, Zahniser served as executive secretary of The Wilderness Society, editor of its journal The Living Wilderness, and later executive director. In addition to Zahniser’s role in The Wilderness Society, he played important roles in other conservation and environmental groups.

Zahniser wrote the first draft of the Wilderness Act in 1956. It was designed to create the legal definition of wilderness in the United States and designate millions of acres of federal land for protection. Ever the masterful wordsmith, he came up with the word “untrammeled by man” to describe the word “wilderness” in the Act.

Yet he believed there had to be a way to balance industry with land preservation. “Our hope in preserving areas free from lumbering,” he wrote in a 1955 policy statement, “is dependent on our ability to achieve prosperous lumbering, based on sound timber management within the forests and woodlots outside the wilderness.”

Despite many people telling him he couldn’t have it both ways, Zahniser fought just as hard for the economic health of the rural Pennsylvania communities as he did for the health of the environment.

For Zahniser, the fight was about to get real. This would not be an easy road.

There was nearly insurmountable opposition to the Wilderness Act and the struggle, at times, was grueling. For starters, the bill was opposed by the National Park Service, the Forest Service, timber, mining, and agricultural interests.

Zahniser refused to take ‘no’ for an answer. He held his ground and made changes. A lot of changes!

His Wilderness Act draft was rewritten or resubmitted 66 times between 1956 and 1964, subjected to 18 public hearings and more than 15,000 pages of testimony. The term “untrammeled”, to describe the wilderness, remained in each draft. Zahniser continued to speak on behalf of the Wilderness Society in advocating the Act, an eight-year-long odyssey in getting it through Congress.

His youngest son, Ed Zahniser, said his father took aspects of his religious background into his advocacy for Wilderness Act. “He lobbied Congress with the dogged persistence born of an evangelist’s confidence in the rightness of the goal,” said Ed. “He believed that with persistency, consistency, and patience, he could convince members of Congress of the essential rightness of wilderness protection. He believed that we are all part of the wildness of the Universe.”

In May 1964, Howard Zahniser delivered an impassioned speech to Congress on the importance of the legislative Act: “I believe that at least in the present phase of our civilization we have a profound, a fundamental need for areas of wilderness – a need that is not only recreational and spiritual but also educational and scientific, and withal essential to a true understanding of ourselves, our culture, our own natures, and our place in all nature.”

As the bill went through revision after revision, Zahniser’s health declined.

It was becoming clear to those closest to him that the process of writing the Wilderness Act was wearing on him. “He’d just go and go, often 30 hours at a stretch without sleeping,” his wife, Alice, later said, “In the end, he just spent himself out.”

On May 5, 1964, one week after his congressional speech, Howard Zahniser died in his sleep of heart failure at his home in Hyattsville, Maryland. He was only 58 and never lived to see final congressional approval of the Act, which was passed by the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives on July 30, 1964.

On September 3, 1964, only four months after Zahniser’s death and following an epic eight-year legislative battle, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Wilderness Act into law with Zahniser’s widow Alice, at the President’s side in the White House Rose Garden. The President presented Alice with the pen he used to sign the Act.

“If future generations are to remember us with gratitude rather than contempt,” said President Johnson, “we must leave them something more than the miracles of technology. We must leave them a glimpse of the world as it was in the beginning.”

Zahniser’s body was returned to the Pennsylvania Wilds where he was buried only 25 feet from his beloved Allegheny River in Tionesta’s Riverside Cemetery.

It wasn’t until 1984 that Pennsylvania won its own federally protected wilderness areas. In the Allegheny National Forest, the 8,630-acre Hickory Creek Wilderness Area and all 368 acres of the Allegheny Wilderness Islands were finally designated as “wilderness” under Zahniser’s Act.

(At right: Howard Zahniser’s headstone is pictured in Tionesta Riverside Cemetery. Courtesy of the Zahniser Family.)

Today, other areas in the Allegheny National Forest such as Tracy Ridge, Cornplanter and Chestnut Ridge await inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System. However, while only the U. S. House of Representatives has the authority to formally approve and issue the Wilderness designation, efforts continue by the Friends of the Allegheny Wilderness to gain that status.

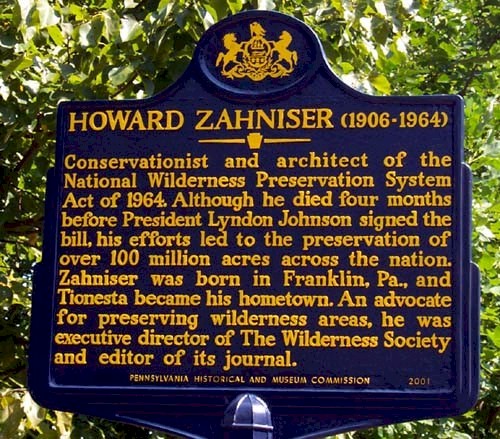

Alongside Route 62 heading into the Allegheny National Forest just north of Tionesta, you will notice a blue and gold Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Marker in Howard Zahniser’s honor. In August of 2001, his children, family members and state officials gathered for a ceremony as the commemorative roadside marker was erected by the Historical and Museum Commission as a memorial and appreciation of Zahniser’s efforts.

Alongside the roadside rumble of passing logging trucks and cars filled with out-of-towners heading to their camps, Zahniser’s son Ed spoke about his father. “He believed that the world is a better place and that we are a better people, despite our all-too-obvious world-altering powers, for boldly embracing the humility to take some of the wilderness and wildness that have come down to us out of the eternity of the past and to project them into the eternity of the future.”

Ed also recalled his father’s words. “As the human population in this country continues to grow, sprawl continues its expansion into open spaces, and natural settings become more scarce by the law of supply and demand. A wilderness, in contrast with those areas, where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

Today, the vastness of protected lands established by Zahniser’s Wilderness Act across our nation totals more than 110 million acres and is acknowledged as the crowning achievement of American conservation, while Earth Day has become a cause for celebration on this, its golden anniversary.

Special thanks to The Wilderness Society, Howard’s son Edward Zahniser and the Zahniser Institute, Ron Heasley of the Forest County Historical Society and Kirk Johnson of the Friends of the Allegheny Wilderness for their assistance and cooperation in writing this article. To learn more about Earth Day, visit The Earth Network.