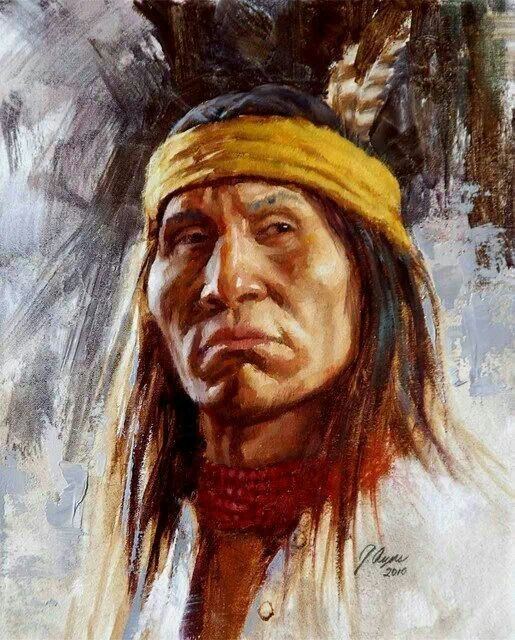

Chief Cornplanter – Warrior of the Pennsylvania Wilds

“Although his skin was uncommonly light for an Indian, his eyes were those of an Indian. For they were dark, intensely dark, even black and, at the same time, strangely luminous. They were deep, absorbing eyes and a great melancholy abided in them. No hint of laughter dwelt there.” – The Hatchet and the Plow: The Life and Times of Chief Cornplanter, by William W. Betts Jr.

Chief Cornplanter

In 1752, along the Genesee River at what is now Caledonia, New York, a Seneca Indian village’s late-night calm was shattered by a newborn baby’s cry. It was a boy.

The mother was Gah-hon-no-neh, Seneca for “she who goes to the river.”, described as a stunningly beautiful Seneca woman. The baby’s father was a handsome Dutch fur trader, John O’Bail, from a prominent Albany, New York family.

While the relationship of Gah-hon-no-neh and John O’Bail, has historical contradictions, such interactions were common among whites and Native Americans in those days.

At birth Gah-hon-no-neh named the little boy Gyantwachia. He later became known as ‘Cornplanter,’ “the one who plants, or, by what one plants.” It was not her first child, she already had a son, Handsome Lake, (Ga-ne-o-di-yo) born in 1735 from an earlier relationship, as well as a daughter, of which little is known.

Handsome Lake

The fathers went their way and Gah-hon-no-neh raised her children Seneca because the mother’s nationality determined the nationality of her children.

Half-white, half-Native American, young Cornplanter grew up fast, learning the way of the woods. With stealth and stamina, his hunting, fishing, trapping and tracking skills were superb.

There was no secret he was different from the other Seneca boys. They called him “half-breed”, and Cornplanter always had to prove himself.

“When I was a child I played with the butterfly, the grasshopper and the frog, and as I grew up, I began to play with other Indian boys, and they noticed that my skin was somewhat different in color from theirs. I asked my mother about it, and she told me that my father was a white man, a resident of Albany.” – (Cornplanter, via interpreter)

Cornplanter never learned English and always spoke through an interpreter.

He was a member of the Seneca Wolf clan with half-brother Handsome Lake, uncle Kiasutha, nephews Chief Red Jacket and Governor Blacksnake.

Cornplanter fought his first battle at 17 and under the watchful eye of uncle Kiasutha became a feared warrior and powerful chief among the Six Nations of the Iroquois, which consisted of the Seneca, Oneida, Mohawk, Onondaga, Cayuga and Tuscarora tribes.

Kiasutha

Four thousand strong, the Senecas were the most populous of all the Six Nations tribes. They were the first Native Americans the arriving colonists met.

Cornplanter fought in the French and Indian War and the American Revolutionary War, both with the British. Preferring his people remain neutral and stay out of the Revolutionary War, he reluctantly accepted the majority decision of the Six Nations League to join the War.

The British won the loyalty of the Senecas and Six Nations by making promises. A lot of promises. They told the Six Nations they would forever keep their land, pledging to protect them with arms and munitions.

Unfortunately, the Brits also plied the tribes with copious amounts of rum and whiskey. Alcoholism became a genuine problem in the Six Nations and among the colonists, too. No one was safe until the whiskey was gone and nobody knew that better than Handsome Lake who later nearly died of alcoholism.

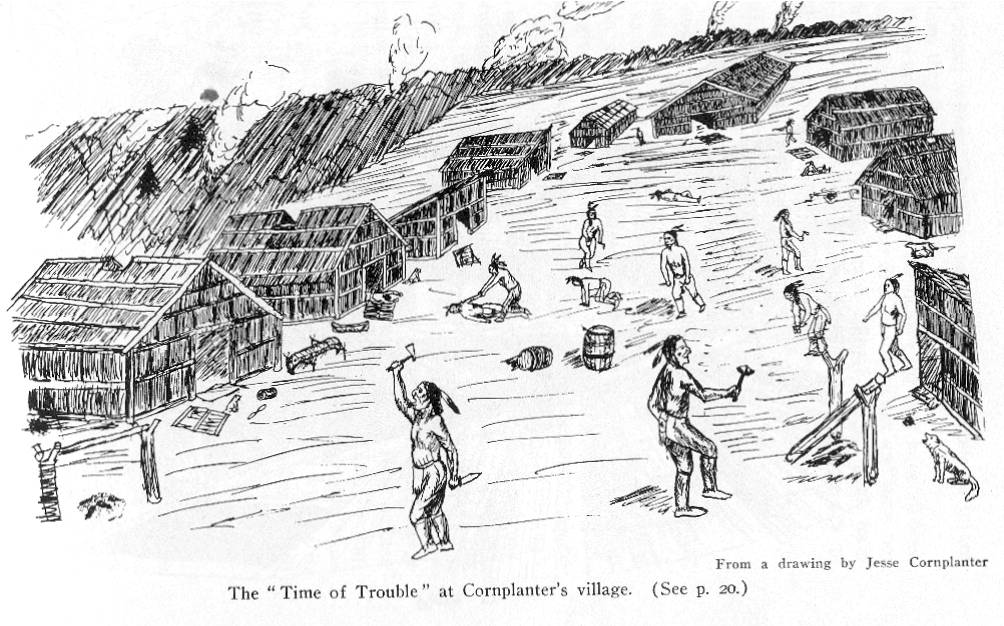

“Time of Trouble” by Jesse Cornplanter

Leading attacks on American settlements in New York and Pennsylvania Cornplanter earned the rank of British Army Captain during the Revolutionary War. But as bloody raids on white settlements increased, the Americans rode roughshod on Seneca lands, burning villages, destroying crops and driving tribes from their homeland.

The end of the Revolutionary War came with the British defeated and the Americans victorious. For the Senecas and the Six Nations, the Revolutionary War was a disaster. The tribes were left with empty British promises and the various treaties eventually saw the Six Nations giving up vast territories to the United States and white settlements.

Clearly, the future of Cornplanter’s people rested with the new United States government. Cornplanter knew that helping the Americans meant helping his people and he cast his allegiance. A little too late, however, to suit Continental Army Commander General George Washington, who continued to support the destruction of tribal villages as punishment for their raids on settlers and siding with the British. Native American losses were heavy.

Surprised that the American outrage had not blown-over, Cornplanter reached out to newly elected President George Washington. Cornplanter called him “The Great White Father,” but the Six Nations had bestowed another not-so-flattering name for Washington; Conotocarious, or “Town Destroyer.”

Cornplanter to President Washington – “What will become of my people?”

“Great White Father, when your army entered the Country of the Six Nations, we called you the Town-destroyer and to this day, when that name is heard, our women look behind them and turn pale, our children cling close to the neck of their mothers.”

“Father, are you determined to crush us? If you are, tell us so that those of our nation who have become your children and have determined to die so, may know what to do. But look up to God who made us as well as you. We hope He will not permit you to destroy the whole of our nation.”- Cornplanter

Cornplanter went to Philadelphia where he met with President Washington and Thomas Jefferson on December 1, 1790. He begged the President for understanding; what will happen to his people under the emerging U.S. nation?

He told the President and Jefferson of personal sacrifices and the plight of his people. He said his family is “lying on the ground in want of food,” that his heart is in pain for them:

“Great White Father, we intended we should till the ground as the white people do. We must know from you, whether you mean to leave us, and our children, any land to till?”

Washington and the Native Americans

President Washington wrote Cornplanter a month later saying he was ordering a halt of Seneca village raids and pledged protection of Native American land:

“Chief Cornplanter, your great object seems to be the security of your remaining lands. I mean to be clear that in future you cannot be defrauded of your lands. That you possess the right to sell, and the right of refusing to sell your lands. That therefore the sale of your lands in the future, will depend entirely upon yourselves.”- President George Washington

Washington also made it clear to Cornplanter that he could not reverse any treaties signed before he took office as President.

Cornplanter’s Tribe Moves to Warren County

Cornplanter and his people moved to land in northern Warren County in the Allegheny River valley. Cornplanter persuaded western tribes for peace with the Americans and for helping to broker this peace, Cornplanter was granted a tract of land – to live on “in perpetuity,” as a show of friendship and gratitude.

Here, Cornplanter took over the leadership role of the Senecas from Kiasutha who died in 1794.

As Cornplanter continued to preach peace with his white brothers and sisters, President Washington sent the Chief a gift – a peace pipe-tomahawk, a reward of friendship and respect.

Peace Pipe – Tomahawk Gift from President George Washington

The gift included a note from Washington:

“It is my desire, and the desire of the United States that all the miseries of the late war should be forgotten and buried forever. That in the future, the United States and the six nations should be truly brothers, promoting each other’s prosperity by acts of mutual justice and friendship.” – (President George Washington to Cornplanter)

Believing the future of his people was ‘the white man’s way’, and at the urging of Handsome Lake and the new U.S Government, Cornplanter invited the Quakers to come teach the Seneca children. Handsome Lake was rebounding from bouts of alcoholism, was becoming legendary as a celebrated Seneca prophet and visionary. He died in August 1815, but Cornplanter continued the Quaker partnership.

The Quakers did not try to convert the Senecas, they merely introduced them to a new way of life, not a new religion. They taught the children English and demonstrated advanced agricultural techniques. Things were going well.

But Cornplanter had a problem. Finding fault with Quaker teachings and fearing a potential “white-man land grab,” he said the Quakers were no longer needed. The Great Spirit “Nauwenneyu” was now speaking to him.

“Nauwenneyu” told Cornplanter to cut ties with the white man, “the conquerors,” and discard all awards, knowledge and everything that had been given to him by the “pale-faces.” Cornplanter broke his sword, trashed his military awards and disavowed the “white way of life” for mistreating his people in the past.

Cornplanter – His Final Years

In his mid-eighties, growing frail and just before he died, Cornplanter described himself this way, “Like an aged hemlock, dead at the top, but whose branches alone were green.”

In his book, Pioneer Life, or Thirty Years a Hunter, Phillip Tome, Cornplanter’s interpreter, described the legendary Chief in failing health:

“His chest was sunken and his shoulders were drawn forward making the upper part of his body resemble a trough. He had but one eye and even the socket of the lost organ was hid by the overhanging brow, resting on the high cheekbone. His remaining eye was of the blackest and brightest hue. Never have I seen one that equaled it in brilliancy. He had a full head of hair, white as the driven snow, which covered a head of ample dimension and admirable shape.”

Cornplanter died at home on his tract in February, 1836, but here is where the Chief’s story gets dicey. There are conflicting reports of his true age. Some swear he was 100, maybe even 105, but most historians agree Cornplanter was born somewhere around 1750 and died in 1836, making him more like 86 or close to 90.

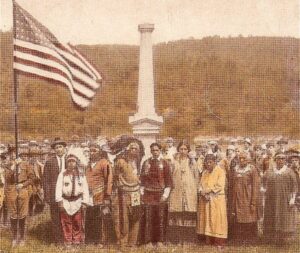

As his people mourned his passing, the Pennsylvania legislature ordered a monument built over Cornplanter’s grave, the first ever such structure erected by a state government in memory of a Native American Chief.

Cornplanter’s original gravesite

Cornplanter Moves to Higher Ground – The Kinzua Dam is Coming

Fast forward to the 1950s. A long drawn out, bitter legal battle was underway as the U.S. Government notified the Senecas it was taking their land along the Allegheny River to build a flood control dam and a reservoir stretching 20 miles up into New York state.

Designed to protect Pittsburgh and downriver communities from costly flooding, the project would consume 10,000 acres of Seneca land. The Senecas must move, their towns will be under water.

The Senecas took the United State government to court in a valiant legal fight reaching all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. but the Senecas lost the battle.

They would be moved onto a much smaller tract of land, ‘The Cornplanter Tract’, up on the Allegheny’s west bank overlooking the new reservoir. Their ancestor’s remains would be exhumed and moved there. In 1964, the United States Army Corps of Engineers removed the Cornplanter burial site monument. Cornplanter’s remains were exhumed from a Seneca cemetery.

Nobody knows exactly whose remains are beneath the monument in that cemetery above the reservoir. With the way the transfer of remains happened, they could be those of another Seneca from the old cemetery, perhaps the great Cornplanter may still lie beneath the waters of the Kinzua-Allegheny Reservoir, say the Senecas.

Cornplanter’s current gravesite, Riverside cemetery

Nobody knows exactly whose remains are beneath the monument in that cemetery above the reservoir. With the way the transfer of remains happened, they could be those of another Seneca from the old cemetery, perhaps the great Cornplanter may still lie beneath the waters of the Kinzua-Allegheny Reservoir, say the Senecas.

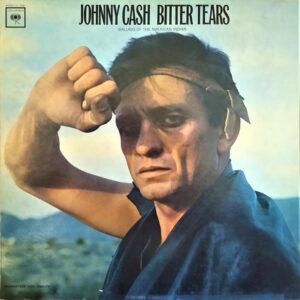

This aspect of Cornplanter history was captured in song by country music legend Johnny Cash who recorded a tribute to Cornplanter; “As Long as the Grass Shall Grow”:

Johnny Cash, the album “Bitter Tears”

The Senecas are an Indian tribe of the Iroquois nation,

Down on the New York – Pennsylvania Line you’ll find their reservation.

After the US revolution, Cornplanter was a chief

He told the tribe these men they could trust, that was his true belief

He went down to Independence Hall and there was a treaty signed

That promised peace with the USA and Indian rights combined

George Washington gave his signature, the Government gave its hand,

They said that now and forever more, that this was Indian land.

On the Seneca reservation there is much sadness now,

Washington’s treaty has been broken and there is no hope, no how

Across the Allegheny River, they’re throwing up a dam,

It will flood the Indian country, a proud day for Uncle Sam.

It has broken the ancient treaty with a politician’s grin,

It will drown the Indians graveyards, Cornplanter can you swim?

The earth is mother to the Senecas, they’re trampling sacred ground,

Change the mint green earth to black mud flats, as honor hobbles down.

As long as the moon shall rise,

As long as the rivers flow,

As long as the sun will shine,

As long as the grass shall grow.

From the LP “Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian,” Performed by Johnny Cash, written by Peter LaFarge.

To this day, Cornplanter’s ancestors call the Kinzua/Allegheny reservoir “Lake Perfidy,” (Lake of Deception), or “Lake of Betrayal” for the way their land and their people’s remains were dug up and carried away to make room for the new dam and reservoir.

The Legend of Chief Cornplanter Lives On

Cornplanter was a huge figure in our history, more than most people realize. He was friends with George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Genealogists trace his blood line to Presidents Teddy Roosevelt, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, George H.W. Bush, George W. Bush and inventor Thomas Edison, all of them through his father’s Danish lineage.

Cornplanter’s legacy is evident across the Pennsylvania Wilds with the Cornplanter State Forest, which covers 1,585 acres in Warren, Forest and Crawford Counties, one of eight state forests in the Wilds.

The 3,000-acre proposed Cornplanter Wilderness Area lies on the Allegheny Reservoir in the Allegheny National Forest next to the Cornplanter Tract. The Warren, PA-based Friends of the Allegheny Wilderness continues efforts toward gaining Federal Wilderness Area designation.

The Seneca Iroquois National Museum, just across the state line in Salamanca, is a beautiful structure dedicated to the culture of the Iroquois with special emphasis on the Seneca.

Cornplanter Council – Boy Scouts of America – The Warren area’s Boy Scout of America organization is known as the Cornplanter Council to honor the famous chief. It is “America’s Oldest Boy Scout Council,” the oldest continuously registered Boy Scout Council in the United States.

Cornplanter Boy Scout Council Shoulder Patch

On September 16, 1966, the Kinzua Dam was formally dedicated. According to an article in the Warren Times-Observer, following ceremonies at the new Dam, there was a gala luncheon celebration in Warren. A quartet of ladies known as ‘The Kinzua Damsels’ entertained Governor William Scranton and other dignitaries with the song “This Is My Country.”

But here, across the PA Wilds’ upper Allegheny River, most of the Seneca Nation, as it was once was, is gone forever. But the legacy of Chief Cornplanter, as a peace-maker, diplomat and devoted Seneca leader, lives on.

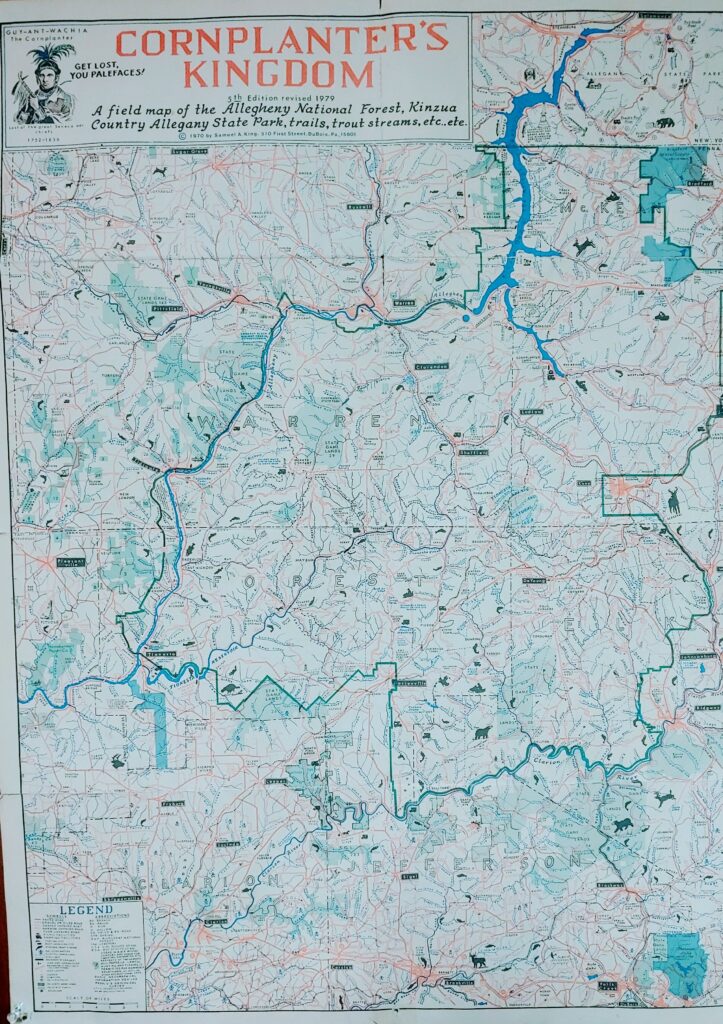

Map of “Cornplanter’s Kingdom”