Pennsylvania Wilds Astronomy Club: Planets more readily visible in fall, winter

By Steve Conard, Pennsylvania Wilds Astronomy Club

Originally published in the Wellsboro Gazette on October 3, 2024

Fall and winter are this year’s planet seasons. Saturn, Jupiter and Mars come to opposition in September, December and January, respectively. Also, Venus reaches its greatest evening elongation, angle distance from the sun, in January as well. The further it gets from the sun, the easier it is to observe.

The earth passed Saturn in its orbit on Sept. 7. While distance to Saturn will slowly increase over the next few months, this is still the best time to view Saturn. By the end of the month, Saturn will be high enough at the end of twilight to see in modest sized telescope until well after midnight. Also, by mid-November our less cloudy early fall nights give way to the much more cloudy winter pattern.

Saturn in the east-southeast at dusk, in the constellation Aquarius. Follow the convenient pointing stars of the Great Square of Pegasus. Pegasus is high in the southeast. Use the two rightmost stars of the square to form a line down, about one and a half times that distance down in that direction. The bright star-like object in that direction is Saturn. It may look cream-yellow to your eye.

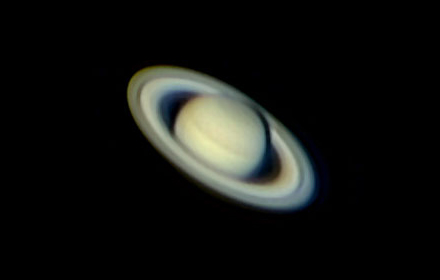

Image: Amateur telescope photo of Saturn – Rochus Hess, Attribution, via Wikimedia Commons

When the Pennsylvania Wilds Astronomy Club has an event viewing Saturn through a telescope, many will remark about the beauty of seeing the ring. Unfortunately, for the next couple of years, the planet’s ring plane is close to the earth’s orbital plane, making the rings much less impressive.

When I viewed Saturn for the first time this year, the rings almost appeared as a line crossing the planet’s disk. It reminded me of a slashed zero when viewed with a low power eyepiece. Others say it looks like a lollipop. Two years from now, it will begin to improve, and in about seven years it will show its best view of the rings again.

Saturn’s spin axis is tilted nearly 27 degrees versus its orbital plane. This is slightly larger than the earth’s nearly 24 degree tilt. For our purposes, you can think of Saturn’s spin axis to be fixed as Saturn orbits the sun, as its axis takes about a million years to wobble or precess a full rotation.

When the spin axis is tilted toward or away from the sun, the rings are well-displayed. As a result, each quarter of Saturn’s nearly 30-year orbit takes our view of the rings from one extreme to the other in visibility.

Image: Stargazers at Cherry Springs State Park in the PA Wilds. Photo by Curt Weinhold.

Since the rings are very reflective and large, Saturn’s overall brightness in the sky varies greatly depending on the orientation of the rings. Six years ago, when Saturn’s rings were fully open, Saturn was about four times brighter than it appears now. The rings are only about 100 yards thick, and at its closest, Saturn is about 800 million miles from Earth.

When the ring’s plane exactly intersects the earth’s orbit as it will this coming March, the rings will briefly become virtually invisible. This year this coincides with Saturn disappearing behind the sun, so there is unlikely to be a reasonable opportunity to see it in this configuration this year.

While the casual observer may be disappointed, for the advanced amateur there are a couple of minor advantages when Saturn is in this configuration. For those who are interested in photographing Saturn’s cloud features and disturbances, less of the planet’s disk is blocked by the rings. Also, in this configuration the larger moons of Saturn can shadow each other, timing these events can potentially produce data to improve knowledge of their orbits.

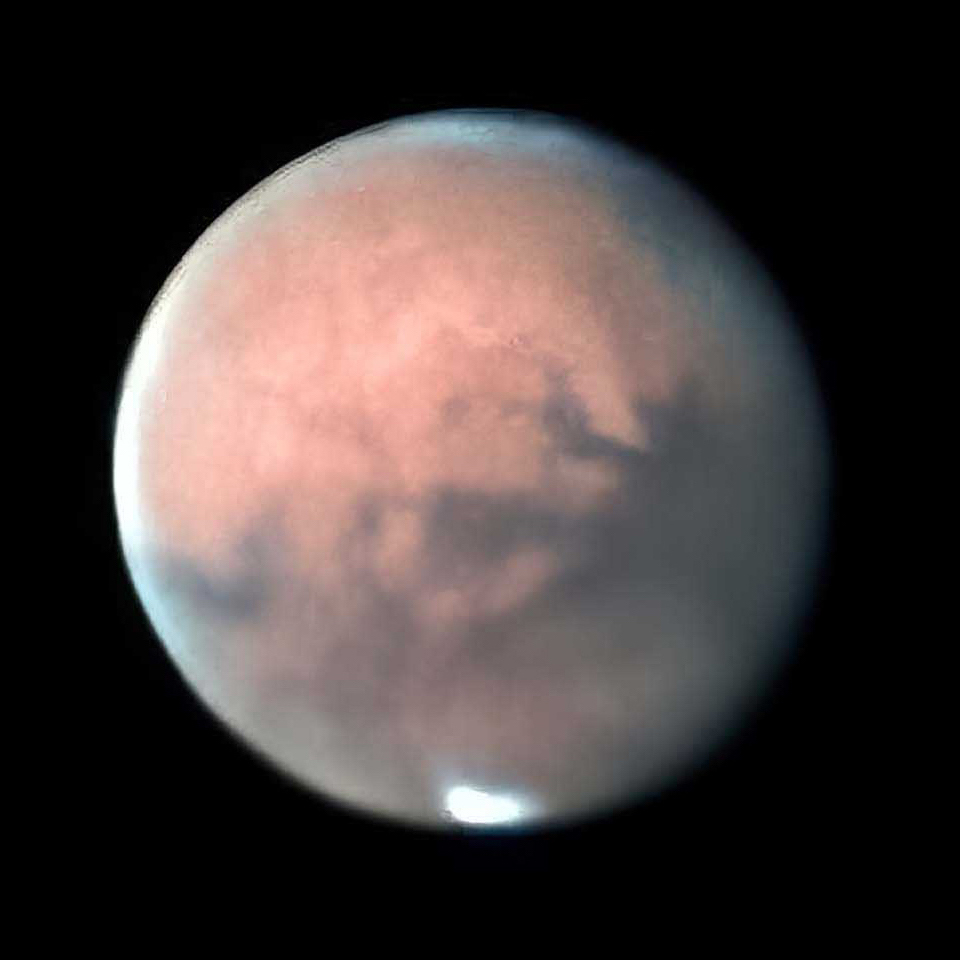

Jupiter varies little in appearance as it rounds its 12-year orbit. Mars varies in how closely it approaches earth, due to the significant elliptical shape of its orbit. The Mars opposition in January is farther from earth than average, resulting in a smaller and fainter appearance.

Image: Amateur telescope photo of Mars – User:Brucewaters, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The positive for those of us in the northern hemisphere is it will be high in the sky, with less of the earth’s atmosphere to blur the image due to seeing. Venus varies how high it is in the sky after sunset depending on the season when the greatest elongation occurs. This year’s is somewhat above average.

Want to join the PA Wilds Astronomy Club?

A new club focused on studying the sky, called the Pennsylvania Wilds Astronomy Club, has formed in north-central Pennsylvania and is now accepting members! The club welcomes members from anywhere in the Pennsylvania Wilds, a 13-county region of Warren, McKean, Potter, Tioga, Lycoming, Clinton, Elk, Cameron, Forest, Clearfield, Clarion, Jefferson and northern Centre Counties.

Additional information on coming events can be found on the club’s website at PAWildsAstro.org.

If someone is interested in hosting an event and having the club set-up telescopes for solar or evening viewing, contact Steve Conard at 410-227-7663 or astro@ptd.net.

About the author: Steve Conard of Pennsylvania Wilds Astronomy Club

The Pennsylvania Wilds Astronomy Club provides education and outreach events for stargazers and dark sky enthusiasts who observe in the 13-county PA Wilds region. Steve recently lived in suburban Maryland, where light pollution fairly severe. Despite the less-than-optimal skies, Steve continued to stargaze and observe. After moving to Tioga County for retirement, he is enjoying much darker skies even though he is less than a mile from downtown Wellsboro. Steve has teamed up with other night sky observers to form the Pennsylvania Wilds Astronomy Club, helping to spread awareness of incredible resource of these dark skies and encourage others to take up the hobby.